Neurodegenerative Disorders: Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s

The “Rising Tide” of Neurodegenerative Disorders: Alzheimer’s Dementia and Parkinson’s Disease

A Growing Problem

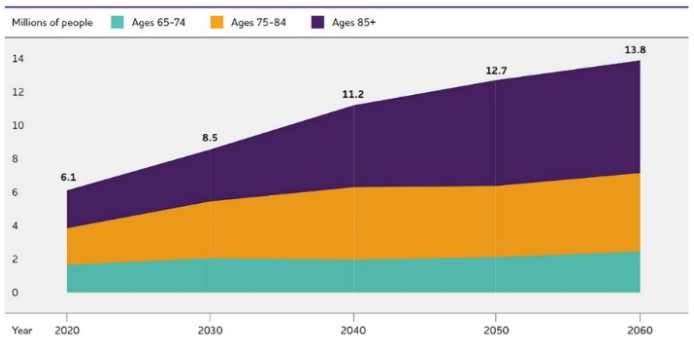

Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s disease are the two most common neurodegenerative disorders in the world. Currently, the global prevalence of Alzheimer’s and other dementias stands at 55 million people, of whom 6.9 million (12.5%) live in the United States [1]. Another 10 million people are living with Parkinson’s disease, of whom 1 million (10%) live in the United States [2]. Given that the United States represents 4.3% of the world population, these numbers indicate that Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are 2-3 times as prevalent compared to the rest of the world. Moreover, both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are doubling in prevalence every 20–30 years [3,4], such that the current trajectory will lead to twice as many people being afflicted by 2060 (Figure 1) [1,5]. Although part of this rise in prevalence can be explained by earlier diagnoses, population aging, and population growth, there is a significant contribution from modifiable environmental factors that remains inadequately addressed [6,7].

Figure 1. Projected number of people aged 65 and older in the United States with Alzheimer’s dementia by 2060 (left) [1], and people of any age with Parkinson’s disease by 2037 (right) [5].

A Complex Problem

While Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s disease are traditionally considered neurological disorders with “hallmark” clinical symptoms, they are far more complex than is commonly recognized and more correctly understood as multisystemic disorders that present with a broad array of neurological and non-neurological symptoms [8-11]. Alzheimer’s is typically diagnosed in the setting of progressive cognitive impairment culminating in dementia [12], which is accompanied by neurodegenerative changes in certain brain regions (hippocampal complex and cerebral cortex), including the accumulation of abnormal protein aggregates (amyloid-beta and tau) [13]. Parkinson’s is typically diagnosed in the setting of a motor disorder characterized by tremor, stiffness, and slowed movements [14], accompanied by neurodegenerative changes in different brain regions (basal ganglia and cortex), including the accumulation of different protein aggregates (alpha-synuclein) [15]. However, it is becoming increasingly recognized that these definitions of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s do not encapsulate the true nature or complexity of these disorders. Alzheimer’s presents with many non-cognitive symptoms, such as loss of smell, pain, gait dysfunction, agitation, aggression, circadian rhythm disruptions, sleep disturbances, and weight loss [8,9]. Likewise, Parkinson’s presents with many non-motor symptoms, such as loss of smell, pain, depression, anxiety, urinary and gastrointestinal dysfunction, sleep disorders, cognitive impairment, apathy, and weight loss [10,11]. Many of the symptoms in both disorders arise from neurodegenerative changes well outside the afflicted brain regions, such as the peripheral, autonomic, and enteric nervous systems [9,11], as well as degenerative changes in non-neurological tissues, such as the skeletal muscles, heart, digestive tract, and urogenital system [16,17]. Based on these facts, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are better understood as complex multisystemic disorders.

Root Etiology of the Problem

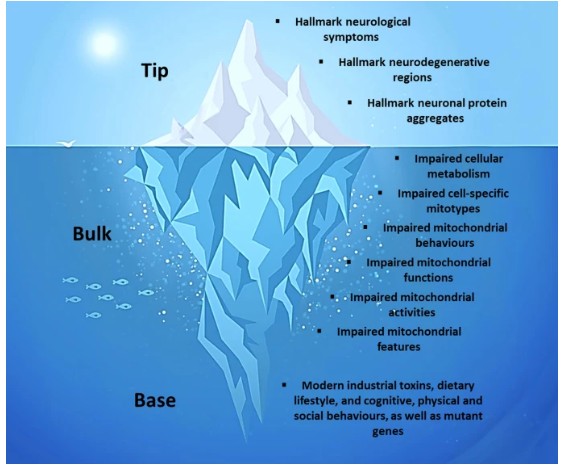

For decades, abnormal protein aggregates have been considered as the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s disease, but treatments based on this hypothesis have collectively failed to produce meaningful clinical outcomes for people with these disorders [18-20]. Alternatively, multiple converging lines of evidence indicate that the multisystemic clinical, anatomical, and pathological features of these disorders represent downstream consequences of a common bioenergetic and metabolic etiology, which may be conceptualized using a “metabolic iceberg” framework (Figure 2) [21]. This framework denotes the clinical, anatomical, and pathological features of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s as the “tip” of the iceberg, which are downstream consequences of impaired mitochondrial biology in the “bulk,” which in turn results after decades of exposure to a variety of triggers at the “base.”

Although traditionally described as cell “powerhouses,” mitochondria are more comprehensively described as cell processors, the principal role of which is to not only generate energy, but also coordinate the flow of energy and metabolism throughout the body [22-25]. Impairment of these processors, along many lines, has been extensively documented in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [26-28]. Impaired mitochondrial biology explains the multisystemic nature of these disorders, as virtually all human tissues contain mitochondria, as well as their predilection for the nervous system, skeletal muscles, and heart, which are especially rich in mitochondria. Ultimately, impaired mitochondrial biology results from decades of exposure to modifiable environmental factors related to modern lifestyles, such as modern industrial toxins, dietary lifestyles, and cognitive, physical, and psychosocial behaviours (and in a small minority of cases, mutant genes) [21]. Among these, the modern dietary lifestyle, characterized by a high intake of processed, carbohydrate-rich foods combined with multiple daily meals and snacks [7], represents a primary driver by repeatedly eliciting blood glucose spikes that lead to excess reactive oxygen species emission, brain insulin resistance, and mitochondrial damage [29,30]. Chronic exposure to these factors both damages and forces maladaptive adjustments by mitochondria, eliciting a trajectory of impaired mitochondrial biology that eventually culminates in the emergence of the hallmark clinical anatomical, and pathological features of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Reframing the Approach

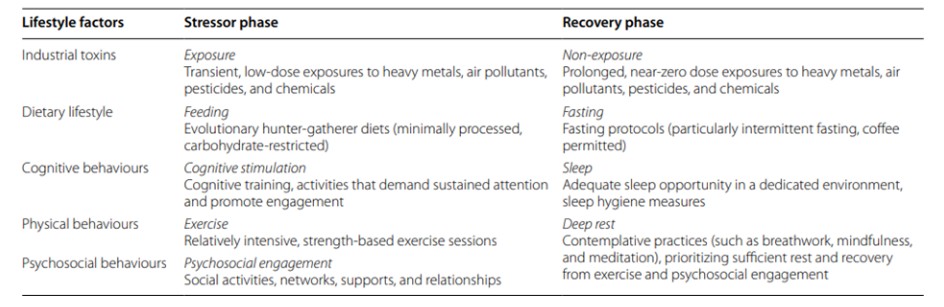

Largely for historical reasons [7], modern approaches to Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s disease continue to emphasize allopathic treatments aimed at targeting and suppressing the clinical symptoms and protein aggregates, yet despite decades of investment these approaches have not produced clinically meaningful outcomes, and may lead to harm [18-20]. Alternatively, the deeper conceptualization provided by the metabolic iceberg framework opens the door for a multisystemic, restorative approach based on enhancing mitochondrial health [7,31]. This may be achieved by lifestyle strategies that encourage “mitohormesis” (improved mitochondrial adaptation and recovery), aiming for a balanced oscillation between mitochondrial stressor and recovery phases (Table 1) [21].

Arguably, the most profound lifestyle changes over the last 50 years relate to the abnormal content and frequency of the modern human diet [7], the alteration of which provides a starting point for a health-oriented, mitohormetic approach that may be crucial in the treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. This can be achieved using “metabolic strategies,” the most impactful of which are low-carbohydrate (including ketogenic) diets and intermittent fasting protocols. Dozens of interventional trials in humans indicate that either strategy can effectively mitigate many of the risk factors (especially, those that comprise the metabolic syndrome) associated with the development and progression of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [7]. Low-carbohydrate diets restrict carbohydrates to 25% or less of energy intake while increasing fat to at least 40% of energy intake, whereas ketogenic diets restrict carbohydrates even further and increase fat to at least 70% of energy intake [32,33]. Either can be synergistically combined with an intermittent fasting protocol, which typically emphasizes fasting periods of 12-48 hours in duration [34]. Metabolic strategies induce a state of “physiological ketosis,” which can rescue brain and mitochondrial energy metabolism by generating ketones [35], a superior energy source for neurons that elicits fewer reactive oxygen species, bypasses brain insulin resistance, and increases the expression of neural growth factors, while also relieving the chronic nutritional overload on mitochondria [34,36,37]. Numerous interventional studies in animals show that ketogenic diets and fasting protocols can benefit brain and mitochondrial metabolism through multiple mechanisms [38], and may slow the neurodegenerative process leading to improved functional outcomes [39]. Consistent with these animal findings, interventional trials in humans, which include several randomized controlled trials, indicate that adhering to a modified ketogenic diet, for even just a few weeks, can improve cognition, function, and quality of life in people with Alzheimer’s [40-43], as well as the motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s [44-47].

Turning the Tide

Unless we stem this rising tide of Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s disease, the ensuing socio-economic impact is poised to exceed the management capacity of healthcare systems in many countries, including the United States. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s both continue to be treated as neurological disorders caused by protein aggregates, which has led to decades of investment into allopathic treatments that have not delivered meaningful outcomes. A different approach is needed, one that acknowledges the complexity and root etiology of these disorders, impaired mitochondrial biology, setting the stage for a multisystemic, restorative approach that can make a meaningful impact on treatment and prevention. Regarding treatment, given the findings to date, further research should be directed to applying cost-effective metabolic and mitohormetic strategies in people with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Regarding prevention, the foundation for metabolic and mitochondrial health begins with public policy measures aimed at mitigating the harmful impact of the modern dietary lifestyle upon the people of the United States. Specifically, the widespread promotion of low-carbohydrate (including ketogenic) diets combined with daily fasting periods of at least 12 hours (ideally, eating once or twice a day, with no snacks) as the normal adult eating pattern would provide a solid foundation for tackling the projected doubling in prevalence of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s by 2060. Ultimately, we can only treat and prevent the rising tide of neurodegenerative disorders by addressing the hidden energetic and metabolic causes that lie beneath the clinical waterline, rather than by focusing exclusively on the visible effects that naturally emerge, in time, above it.

Dr. Matthew Phillips, a clinical and research neurologist at Waikato Hospital in New Zealand, is bringing new hope to the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders through groundbreaking clinical trials exploring the therapeutic potential of metabolic interventions, particularly fasting and ketogenic diets, in Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other challenging neurological conditions.

Article Reference: Neurodegenerative Disorders, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s – References