Appalachia

The Obesity and Diabetes Epidemics in Appalachia

People are fed by the food industry, which pays no attention to health, and are treated by the health industry, which pays no attention to food.

—Wendell Berry, author and sixth-generation Appalachian Farmer

The Nutrition Transition and Fatalism

Modernization, urbanization, economic development, increased wealth, poverty, and other factors lead to shifts in diet, referred to as “nutrition transitions.” Has there been a nutrition transition in Appalachia in the last 60 years? What was it? Does this relate to the obesity and diabetes epidemic in Appalachia? Are there differences here that are unique in the world’s obesity epidemic?

Since the conditions of obesity and diabetes continue to rise now at an accelerated rate all we can do is present some historical data and create hypotheses which would need to be tested. Creating an ideal food environment and physical environment incorporating best principles of generations ago would take a magic wand experiment. Our roles as clinicians and academics compel us to use the best clinical evidence and experience to shape our thoughts and actions.

“Fatalism” is a common theme when the research and clinical groups discuss health disparities in Appalachia versus other regions, which might have similar social determinants of health.

Malcolm Gladwell’s 1998 article, “Pima Paradox,” witnessed the same phenomenon: “People who work with the Pima of Arizona say that the biggest problem they have in trying to fight diabetes and obesity is fatalism–a sense among the tribe that nothing can be done, that the way things are is the way things have to be” [1].

The Epidemic and Pandemic with No Flattening of The Curve

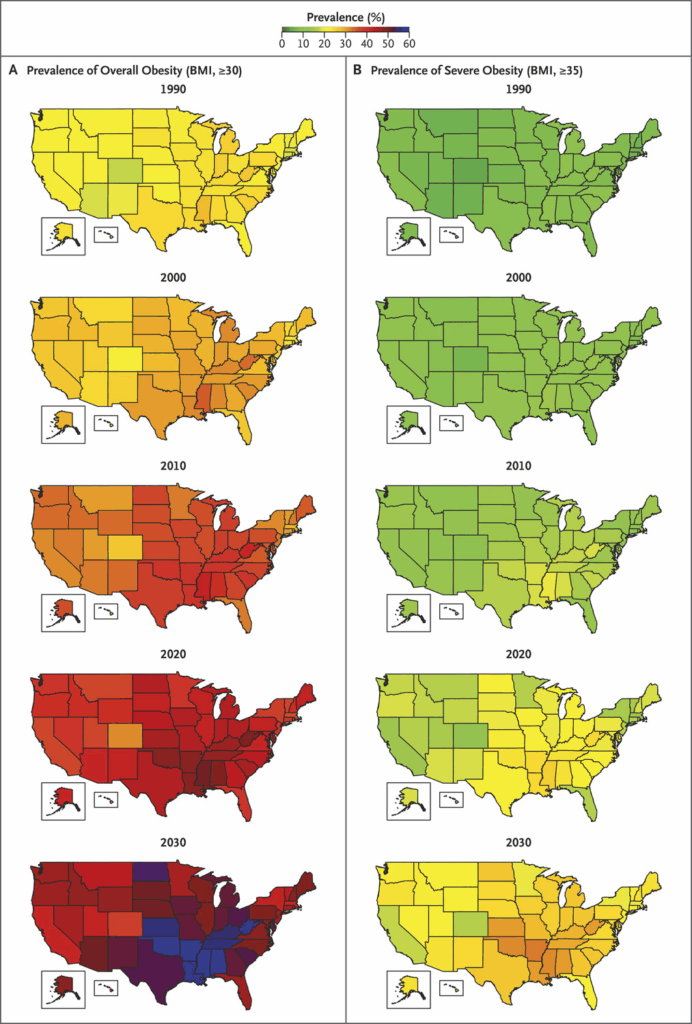

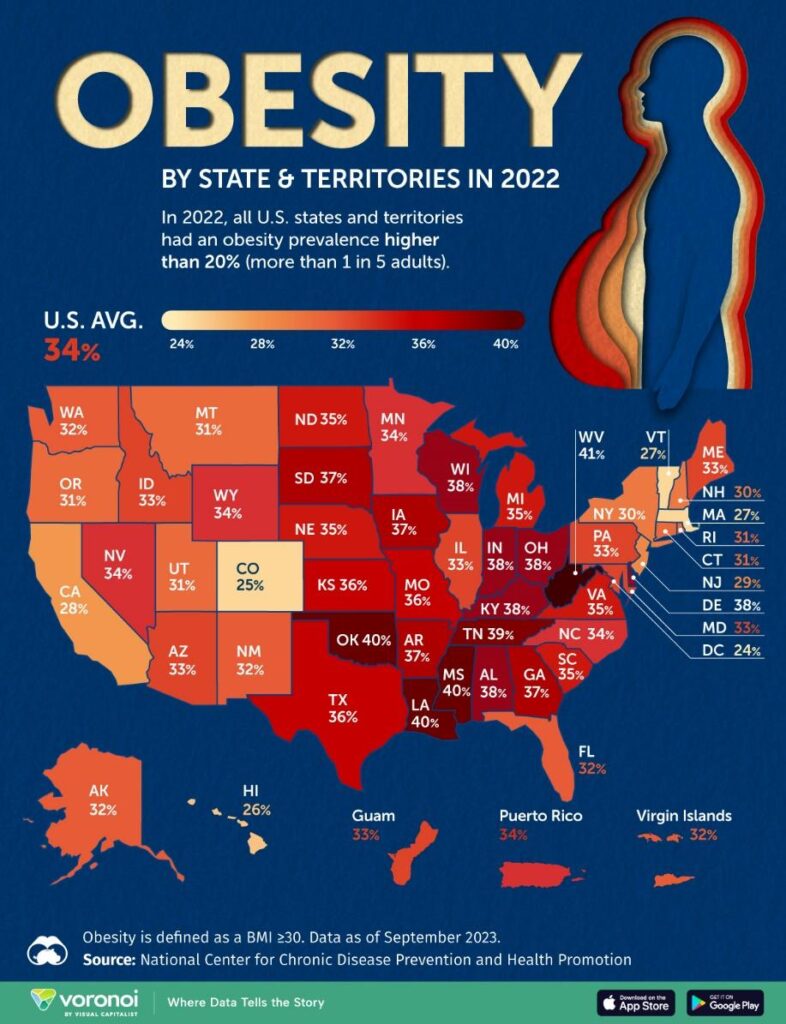

The coronavirus added more flame to the Appalachian region’s already poor health. Americans with obesity, diabetes, heart disease and other diet-related diseases were about three times more likely to suffer worsened outcomes from Covid-19, including death.[2]. Had we flattened the still-rising curves of these conditions, it’s quite possible that our fight against the virus would look very different. West Virginia has the highest obesity (41%) [3] and diabetes rate (15.9%) [4] in the country.

Estimated Prevalence of Overall Obesity and Severe Obesity in Each State, from 1990 through 2030 [5].

Could it be Food Insecurity or Just Cheap Carbohydrates and Fats?

Food insecurity describes a household’s inability to provide enough food for healthy living. That could mean both having insufficient supplies, but also a lack of the variety of foods, including meats, eggs, cheeses, and fresh vegetables, that are needed to provide the right nutritional balance. The regions where access to real food is strained are called “food deserts” and these may exist in both urban and rural centers. Unfortunately, those with food insecurity living in food deserts have some of the highest rates of obesity and diabetes.

Feeding America, the country’s largest hunger-relief nonprofit organization, estimated roughly 17 million more people became food insecure in 2020, bringing the total to 54 million, including 18 million children [6].

Anahad O’Connor uncovered a government report exposing that sugary soda is the most popular item in the shopping carts of families that receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and wrote about it in an article for the New York Times titled “In the Shopping Cart of a Food Stamp Household: Lots of Soda”. Other ultra-processed foods (such as sugary cereals, chips, packaged snack foods) were also high on the purchase list. Many in the Appalachian region rely on SNAP for food and may be suffering health effects of these choices [7].

Food insecurity and obesity have many of the same risk factors (e.g., income or race/ethnicity) and often coexist in populations. Researchers have hypothesized several mechanisms for how food insecurity might lead to obesity. These include inadequate nutrient rich food affordability and/or availability; stress and anxiety about food insecurity that generate higher levels of stress hormones, which heighten appetite and may also cue the body to store higher fat amounts in response to reduced food availability.

The alternative hypothesis is refined carbs and seed oils are the cheapest foods. It’s what you eat when you are food insecure. Of the three macronutrients- protein, fat, and carbohydrate- processed carbs such as white flour and sugar as well as processed seed or “vegetable” oils are the cheapest. Protein costs more. Protein is the most nutrient dense. Protein makes you full [8]. When these inexpensive sources of carbs which raise insulin are then combined with the calorie dense and nutrient poor seed oils it sets the table for obesity, whether one is food insecure or not.

Populations that eat the Standard American Diet (SAD) develop Western diseases (obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and many cancers) at younger and younger ages. Is it a single culprit or the entire way of eating – processed oils, refined grains, and sweetened beverages with a void of food that is natural, fresh, and locally sourced. These food choices are not unique to SNAP families.

Some may argue that there is a “bliss point” in these processed foods [9]. That may be true, but other cultures such as the French find “bliss” in delicious fresh foods raised and grown locally. Perhaps the “bliss” of food in Appalachia has shifted from a family cooked locally raised meal to one of fast and processed foods. In speaking with several citizens and health providers throughout the region one common theme was the disappearance of the family garden as well as many small local farms with more shopping at local dollar stores and convenience stores versus grocers. The other culprit was the introduction of sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) combined with lots of other sources of sugar.

The Case Against Sugar

Appalachia has deemed opiates and tobacco as toxins to human health. We could ask, “Is sugar a toxin?” If so, imagine a toxin of equal or higher pathology than opiates and tobacco, and you have sugar. And what if tobacco and opiates were as affordable, accessible, and acceptable as sugar? This used to be the case with tobacco before regulations. In the 90s there was high accessibility and acceptability of using opiates.

Cornell University’s Dr. Lewis Cantley is one of the world’s leading researchers on the effects of sugar on cancer and other diseases. He grew up in rural West Virginia and now in his work shares the science about his observations.

I noticed the change in obesity in West Virginia in the 1970s. I think WV was ahead of the nation in this regard. I was in graduate school at Cornell (Ithaca) in the mid-1970s and had been away from West Virginia for several years. I was struck by how much weight my high school friends had gained in that short period of time and noticed that they we are drinking far more commercial sugary drinks.

As a physician in West Virginia, I visited elementary and middle schools for a formative research project funded by the Benedum Foundation. The chocolate and strawberry milks have 6 to 7 teaspoons of added sugar (WHO top limit 6 tsp a day for kids [10]) and the kids average 2 servings a day of the milk alone. It was hard to find a child drinking skim or lowfat. There was no whole milk. If you ask the kids “why?” The answer in their language “the skim milk tastes like chalk”. We are feeding the kids this toxin under the USDA guidance.

What is Unique to Appalachia?

Regional surveys suggest that Appalachian children consume three to four times the amount of sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) as their non-Appalachian counterparts. Melissa Olfert and her team at West Virginia University identified the presence of metabolic syndrome to be 15% among students which is shockingly high compared to matched universities in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast. [11]

What was then: the West Virginia one room school

From the online West Virginia Encyclopedia [12]:

“4,551 schoolhouses dotting the Mountain State during the 1930–31 school year. Their number declined with the adoption of the ‘‘county unit’’ school system in 1933 and as better roads allowed for easier automobile and school bus travel.”

“In their heyday, one-room schools were generally located within two or three miles of their students, who usually walked to school.”

“……. Morning and afternoon recesses saw students playing such games as ‘‘Ante Over,’’ which involved throwing a ball over the school’s roof and back, ‘‘London Bridge,’’ ‘‘Kick the Can,’’ ‘‘Drop the Handkerchief,’’ and ‘‘Go Sheepy, Go.’’ A full hour was given over to lunch, prepared at home and often carried to school in a tin lard bucket.”

What was then: Appalachian Food

“In our area, we primarily ate what we grew in our gardens, and our meat came from our farm,” said Elaine Irwin Meyer, president of the Museum of Appalachia. “Most folks had hogs, so pork was abundant. We would can our sausage, hang our hams in the smokehouse to cure and use the fat to season our vegetables. It has been said that the only part of the hog that was not used was the squeal!”

“……There wasn’t anything that would qualify as fast food—unless it was something that could be plucked right from the ground or tree and eaten.”

“When I think of Appalachian food, I think of long simmering pots of food lovingly prepared by women who enjoyed creating a wholesome meal for those they loved,” Meyer said. “There was nothing quick about this kind of food preparation, and maybe that aroma created an anticipation that made the meal even more appealing. Mealtime was a time of sharing and listening and just being together time for busy families.”

Historical data on the nutrition status of Appalachian children is sparse and no doubt there were deficiencies many because of living conditions and poverty. The 1955 “Nutritional Status Studies in Monongalia County, West Virginia” is the best document of record. The findings “indicated that dietary deficiencies of ascorbic acid, vitamin A, riboflavin, and iron existed” [13]. Other findings: “Medical inspections of children in West Virginia revealed relatively few physical signs of severe nutritional deficiencies” and “children living in small mining or industrial communities had poorer diets than did those living in urban areas around Morgantown, West Virginia.”

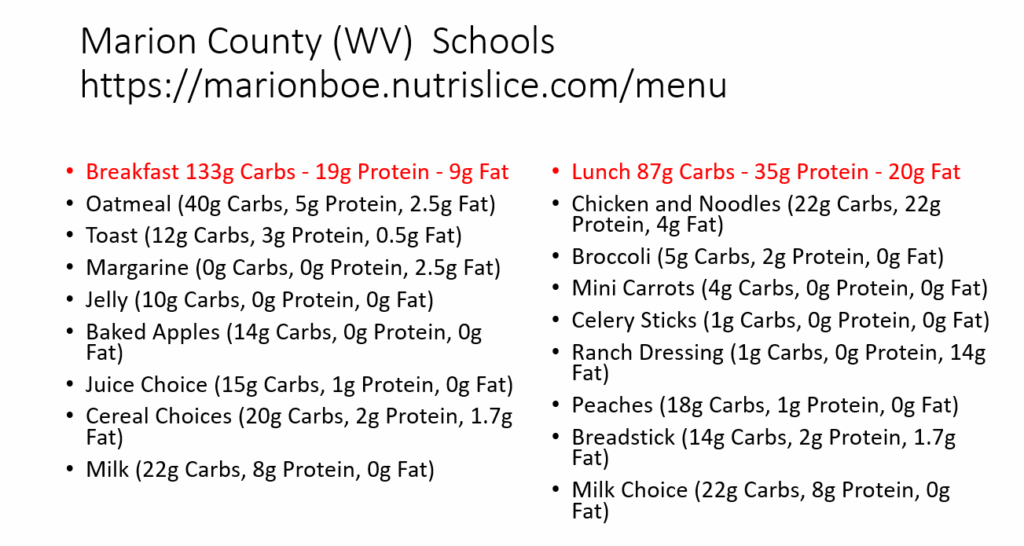

What are children now having in their school lunch?

Marion County (WV) Schools has complete breakfast and lunch menus, and you can print out the CHO/PRO/FAT counts: https://marionboe.nutrislice.com/menu

Pick a random day at Blackshere Elementary: 200 grams of carbs with just breakfast and lunch. That’s a lot of processed carbs for elementary kids. Then they often go home to Mountain Dew and pizza. Lots of fat too and it’s almost all seed oils. The scientific recipe for obesity: processed carbs + sugar + seed oils + almost no natural fats or proteins [14].

Carolyn Mills is 78 years old now retired for several years. She was the director of the kitchen at one of our local middle schools from the mid-60s to the mid-90s. Before USDA Dietary Guidelines in 1980 (which mandates what is served to children) the cooks in the cafeteria basically made homemade recipes that they had in their families and cooked them in quantities for the children. Kids drank whole milk. Eggs were real eggs. After 1980 in her words “the state gave us all the recipes and we had no choice but to make them” [15]. Everything changed. Butter was switched out for margarine. Whole milk was substituted for 2% and chocolate milk. Whole wheat flour substituted for the flour that they used before.

Carolyn reflects: “We could not season anything since salt was reduced and that in combination with the whole wheat flour, which the children hated, put most of the school lunches in the trash can.” She said even her own children packed lunch on this menu as they could not stand the school lunch. In her words she also said: ” if you had left us be, the kids wouldn’t be obese”[16].

What factors are contributing to the higher percentage of obesity and diabetes in Appalachia, especially among the youth? Many health and academic leaders in the regions have studied the issues.

The best assessment of regional differences comes from Dr. Laureen Smith now of Ohio State University who grew up in Appalachian Southeast Ohio and was lead author of Rates of Obesity and Obesogenic Behaviors of Rural Appalachian Adolescents: How Do They Compare to Other Adolescents or Recommendations?

According to this article: “About 30% of the adolescents were extremely obese. This rate is more than double the rate of other adolescent populations. Our rural Appalachian males’ extreme obesity rate (13%) was more than double the rate of male adolescent populations of similar age (5.9%).” Consider that 94% in her study consumed at least one sugar sweetened beverage a day, and most consumed several. There is much more to the story. In my conversation with Dr. Smith, she described many regional contributions to this issue, such as cheap junk food availability, reduced walking or biking to school, the lack of physical activity during and after school, less family meal cooking, fast food, vending machines in schools, and many other factors [17].

Another researcher, Dr. Kelli Williams of Marshall University, wrote in a 2008 paper Cultural perceptions of healthy weight in rural Appalachian youth gives insight into the perceptions amongst peers and parents on obesity [18]:

“Youth in rural Appalachia present similar perceptions about weight as other children; however, differences in perceived healthy lifestyle habits and a general acceptance of a higher average body weight present additional challenges to addressing the increasing problem of child overweight. Despite the relative isolation of many of these communities, the media has a profound impact on weight valuation that has been intertwined with school-based health education and cultural values of health.”

In our correspondence, Dr. Williams observed similar factors and behaviors to Dr. Smith: “…I think dependence on quick/easy, less nutrient dense meals is a big part of the problem, especially a fast-food culture. Research supports that meals eaten away from home are less nutrient dense. In my experience with clients/patients, it seems that less and less people are making time for family meals, and even more aren’t preparing foods regularly at home” [19].

On the topic of purchasing food: “There are certainly a lot of food deserts in Appalachia. I think this could certainly contribute to the problem. People are purchasing food for meals at gas stations, etc. I think we have easy access to SSBs and other less nutritious foods” [20].

Lara Foster, who was a colleague on the Benedum school project addressing the food environment of children, also spent a year traveling around West Virginia on a project titled “Sharing Their Own Stories” for West Virginia Medicaid. She witnessed throughout these travels that McDonalds and Dairy Queen were in every small town and the lines around these places were long. There was also minimal to no active transportation. She works as an EMT now at a volunteer fire department and it is acceptable to be what is termed a “Jolly Volly” which is an overweight volunteer firefighter. Firefighters, law enforcement, and first responders unfortunately have the highest rates of obesity of any profession as well as the highest cardiovascular event rates [21]. These dedicated citizens certainly have not become this way out of some personal flaw of lack of willpower, overeating, and laziness. There is something more in the environment that must be uncovered [22].

Image: The Future is Now: A co-existing Sweet Shop and Pharmacy in Rural Tennessee

Mountain Dew Mouth

In 1974 T.L. Cleave wrote a book entitled The Saccharine Disease – Conditions caused by the Taking of Refined Carbohydrates, such as Sugar and White Flour. In this book he states “The clear evidence is that ill health (obesity/diabetes/heart disease/ certain cancers) appear in pre-industrial communities immediately after the introduction of sugar, white flour, and other refined carbohydrates. There is no proven link to any sudden increase in habitual fat intake” [23].

Cleave went on to suggest that tooth decay provided the obvious clue to the cause of what was termed Western Diseases. Appearing early in life, he said, it was the equivalent of the canary in the coal mine and foretold the coming of the entire spectrum of Western Disease [24].

Another forbearer of the connection of dental health to human health was Cleveland dentist Dr. Weston Price (1870-1948), who has been called the “Isaac Newton of Nutrition.” In his search for the causes of dental decay and physical degeneration, he turned from test tubes and microscopes to unstudied evidence among human beings. The world became his laboratory. In the 1930’s Price traveled the world over to study isolated human groups, including sequestered villages in Switzerland, Gaelic communities in the Outer Hebrides, Eskimos, and Indians of North America, Polynesian South Sea Islanders, African tribes, Australian Aborigines, New Zealand Maori, and the Indians of South America. Wherever he went, Dr. Price found a strong association of beautiful straight teeth free of decay to robust healthy bodies free of disease. When native peoples turned from traditional diets, all of which included animal products, to modern processed diets their teeth and health suffered [25]. In 2017 the massive PURE study of over 130,000 people from 18 countries validated what Dr. Price discovered nearly 100 years ago that animal products are nutrition keystones of a healthy human [26].

In the modern day, we are witnessing a condition termed “Mountain Dew Mouth”. In West Virginia and other regions of Central Appalachia, the consumption of these beverages has created an oral health crisis. A recent House Bill to increase tax on SSBs succinctly shares the problem. The bill did not pass:

According to research done by the American Dental Association, 65% of children in West Virginia ages 3 to 7 suffer from tooth decay. To put this statistic in perspective, a CDC study from 2011-2012 found that 37% of children across the nation ages 2 to 8 have experienced tooth decay. Therefore, the rate of tooth decay for children in West Virginia is almost twice the national average [27].

Mountain Dew has its roots in the 1930s with Barney and Ally Hartman, two brothers from Georgia who moved to Tennessee. The Hartman’s were apparently big whiskey drinkers and looking for a proper mixture to substitute for their favorite one which they could not get in their new city. They created a carbonated lemon-lime drink to mix with the booze and called it Mountain Dew, which is slang for [28].

After a few years of making and drinking Mountain Dew on their own they decided to rebrand their beverage as an Appalachian thirst quencher and gave it silly slogans like “ya-hooo!” and “it’ll tickle your innards.” They added cartoonish country folk and started selling Mountain Dew in green bottles [29].

In the 40s and 50s they were not having much success, and the company was bought up by the Tip Corporation who then sold it to PepsiCo. With some orange flavoring, the lime green coloring, and rebranding without the hillbilly image the new Mountain Dew was born and took off.

There is even a suggestion that Appalachia has a distinct culture of sipping soda constantly throughout the day. “Here in West Virginia, you see people carrying around bottles of Mountain Dew all the time — even at a public health conference,” says public health researcher Dana Singer of Parkersburg, WV [30].

As the beverage companies continue to deflect claims that the beverages affect oral health, dentists such as Dr. Frank Rainieri who has been practicing 25 years in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia differs in his opinion. When he moved from New Jersey to West Virginia he noticed an immediate difference in oral health. Through his career he has loved his job as people in need really needed him and he could always help as an independent small-town dentist.

“The sugars feed on the bacteria to help create an acidic environment which is toxic to the enamel of the teeth and causes demineralization. The constant sipping inhibits the mouth’s ability to neutralize. Water drinking through the day has that neutralizing effect. We see similar effects with meth mouth where the neutralizing saliva is stripped, leading to tooth decay and cavities ”[31].

Frank himself has realized the destructive effects of sugar and processed carbohydrates in his own health, and he has reversed his Type 2 Diabetes by removing this part of his diet and has lost about 50 pounds and restored his health.

In 2019, I participated in an all-day symposium on Diabetes and Oral Health hosted by West Virginia University Dean of Dentistry Dr. Foti Panagakos. One of the key takeaways was that dental disease contributes to inflammation and oxidative stress throughout the body which in turn increases the insulin resistance. The oral microbiome has trillions of bacteria, which can either be an ally or a foe to optimal digestion. They are impacted by what we put in our mouth. In addition, worse glucose control and worse diabetes creates a sick oral environment and inhibits the healing of dental disease processes. It is a vicious cycle.

Advancing Metabolic Health in a West Virginia Community

It is a privilege to serve in a small West Virginia town, collaborating with partners to improve the health of our community. My background in preventive medicine stems from 29 years of service in the U.S. Air Force, where risk assessment was a primary focus, demanding much of our time and expertise.

For the past 15 years, my clinical and academic focus has been on metabolic syndrome—also known as insulin resistance—a key contributor to numerous chronic diseases. This field was pioneered by the late Gerald Reaven, who published over 1,000 papers on the subject. I first contributed to this area of research in 2004 [32] and have since worked to educate healthcare professionals on the importance of identifying and reversing this condition.

In our practice, we recognize that nearly 80% of our patients likely have metabolic syndrome. It is our duty to explain this condition in clear, simple terms and empower patients with the knowledge to reverse it. Just as we address smoking’s impact on heart and lung health, we must take the same proactive approach with metabolic syndrome—identifying risks, providing guidance, and supporting patients in making meaningful changes. Education and outreach remain the cornerstones of this effort.

My hospital, Jefferson Medical Center serves as a model for applying effective dietary interventions to diabetes and other metabolic diseases. Despite the American Diabetes Association (ADA) now recognizing a low-carbohydrate diet as the most impactful for blood glucose control [33], traditional hospital “ADA diets” still include 60 grams of carbohydrates per meal. At our hospital, we reduced this to 10 grams for patients who opt in, pairing it with education and ongoing follow-ups to ensure sustained success. This cultural shift in our small hospital also paved the way for the removal of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) in January 2018, reinforcing our commitment to metabolic health and disease prevention.

Bright Spots: People and Programs Making Change. The Call to Action

In Appalachian and other regions where diabetes and obesity have taken root these conditions have become associated with the “diseases of despair”. They are framed as progressive disorders often requiring lifetimes of medication. Patients hear of the increased risks of heart disease, blindness, kidney disease, neuropathy, loss of limbs, increasing infections, and stroke. Every year we hear the conditions are becoming more prevalent, but why? Citizens have heard of lifestyle modifications and choices but struggle to start or maintain change. The outcome is increasing morbidity, mortality, and healthcare cost. And there is the often-discussed term of “fatalism”.

We wish to reframe obesity and diabetes with hope. We must present these conditions as preventable and reversible with lifestyle change that is achievable and enjoyable. Citizens can lead a lifestyle free of medications and many times reduce them. The multitude of complications can be prevented. The outcome in this way of thinking is improved health and well-being and significantly reduced health and social cost. Beginning a life free of dieting and indulging oneself in health.

One such organization giving hope is Try This West Virginia. Founded by West Virginia native and former Charleston Gazette writer Kate Long, this grass roots organization now nearly 10 years in existence highlights small community initiatives which can be replicated for wider change. In her words the goal was and still is “to help knock West Virginia off of the worst health lists”.

Kate wishes to give people the tools so they can do it themselves. Small mini grants, conferences, and workshops enable citizens. These include community gardens, community fitness initiatives, school-based mentorship and support, and an annual conference attended by 100s so citizens can share successes and challenges. Five years ago, the organization hosted a medical conference in West Virginia on diabetes and obesity and had the courage to bring in Gary Taubes as the keynote. His scientific and historical perspective on the toxicities of sugar challenges some sectors of medicine and public health [34].

What is unique about Ohio State Researcher Dr. Laureen Smith is she is not just observing the lives, behaviors, and poor outcomes. She is taking action with innovative programs mostly focusing on peers and mentors to shape youth. One example is Sodabriety [35]. A fun and creative teen advisory council helping their peers reduce sugary drinks. Dr. Smith reflects: “A child’s odds of becoming obese increases almost two times with each additional daily serving of a sugar sweetened drink, and Appalachian kids drink more of these types of beverages than kids in other parts of the country. Sugar sweetened beverages are the largest source of sugar in the American diet. For some teens, they account for almost one-third of daily caloric intake, and that amount is even higher among Appalachian adolescents. If we can help teens reduce sugared beverage intake now, we might be able to help them avoid obesity and other diseases later in life” [36].

After the month of Sodabriety the average number of daily sugared drinks dropped from nearly 2.5 servings to 1.3, and the number of days students reported having a sugary drink dropped from 4 days a week to 2 days. Water consumption increased nearly 30 percent from baseline. She returned a month later and the behaviors were still intact. The study makes the case for more student-designed and student-led interventions.

Another peer intervention of Dr. Smith was “Mentoring to Be Active” [37]. In this study the group of obese and extremely obese youth led by peers lost more weight than programs led by teachers. The intervention matched peers mostly of similar BMI focusing mostly on walking and outdoor activity as well as body weight exercises.

For Appalachian and other communities with limited resources we must look to apply what is termed minimally disruptive medicine. This concept has been written about and discussed by Dr. Victor Montori of the Mayo clinic[38]. The burden of illness (the pathophysiological and psychosocial impact of disease on the sufferer) has its counterpart in the burden of treatment (the workload delegated to the patient by health professionals, which may include self-care and self-monitoring, managing therapeutic regimens, organizing doctors’ visits, tests, and insurance).

For any chronic condition we must support patients with interventions and treatments that fit into the context of their lives. One person who understands this concept and has seen the adverse effects of intensified medical therapy is Bob Shefner, who runs the Community Ministries Food Bank in Charles Town, West Virginia. A survey conducted by WVU Medicine shows that about 30% of our food pantry users have diabetes. Adding to this already large number are an additional 20% who have been diagnosed as being prediabetic. These were just those who had medical care to be aware.

About 5 years ago Bob started learning more about the signs of diabetes and was witnessing some of his customers making incredible change. He transitioned from his standard diet, filled with cookies, to one that he would suggest a patient with diabetes eats- a real food low carb diet. He was prediabetic at the time and has reversed his condition and lost belly weight. When I met Bob at the ministries, we hosted a teaching session where an African American client improved from a hemoglobin A1c of 23 range (an average sugar of 700 mg/dl blood sugar for 3 months) down to a normal A1c of 5 by changing the diet.

Bob’s client’s all have food insecurity, many are homeless, and all are seeking basic needs. Many do not have the capacity to adhere to complex medical regimens and multiple specialty appointments. Bob has designed initiatives within the community ministries to better serve the diabetes population with foods appropriate for them- foods low in sugar and processed carbohydrates. He receives donations of vegetables and uses funds for eggs and cheese and meats which can support better diabetes control. He also hosts cooking classes within the ministry using the basic ingredients they have on the shelves. Staff are trained with carbohydrate content food lists to help people make better selections. Most importantly Bob believes people need support and offers it to all as best he can [39].

Lance King Paul is a West Virginian who grew up in rural Mississippi with the same social determinants present in Appalachia. Economic hardship was common and the food he grew up with was inexpensive and convenient. During the 70s when he was a child Kool Aid was the main drink. Lance went on to work several years in Germany where the lifestyle was more active, communities more walkable, and food more local and fresher (even at the local Aldi). He returned to the States eventually moving to West Virginia and during this time while living off the acceptable pattern of sugar sweetened drinks and fast food his weight increased to 400 pounds. By his mid-40s Lance was fully diabetic and on over a dozen medications. After a couple hospitalizations for weight related conditions, he was considering gastric bypass. As a spiritual man he states that by “divine intervention” he learned of a local low-carbohydrate support group meeting and attended with his wife. This changed his life. He immediately got off the dietary sugars and carbohydrates and rapidly started losing weight and coming off medications. Today he is 240 pounds, takes no diabetes medications, maintains completely normal blood sugars, and mentors others to make this change. He has hope for a long and healthy future and to enjoy the retirement he has earned for over 20 years of service with the U.S. State Department [40].

Dr. James Bailes, Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Marshall School of Medicine, is a bright spot. Dr. Bailes practices pediatric endocrinology in Huntington WV which was once renowned as the most obese and unhealthy city in the country. Celebrity Chef Jamie Oliver produced a documentary and a TED talk on youth and food there.[41] Dr. Bailes had his own nutrition transition. A student had lost significant weight on a low carb diet and another student reviewed his charts and reported that obesity patients were not losing any weight. So, he read and studied the science and changed his practice. Transformed patients led him to write “No More Fat Kids: A Pediatrician’s Guide for Safe And Effective Weight Loss” (AvantGarde Publishing 2006) as well as other scientific papers, two of which we published together [42] [43] [44].

Angel Casto is a master’s level, registered and licensed dietitian at the WV Children with Special Health Care Needs program. For the first twelve years in practice as a registered dietitian, Angel followed the USDA Dietary Guidelines. And yet, she struggled with her weight. It was after hearing a low carb talk at the state dietetic conference that lit the fire that would become her new way of life. She has had great success with a low carb diet over this past year and she is now a firm believer in the importance of metabolic health. Angel reflects: “Finally throwing out the conventional lessons I’d learned and seeing for myself there is a better way than >50% of total calories from carbohydrates, has been so liberating for me personally.”

To close this essay, I am going to the insight from Craig Robinson, who directs the network of Cabin Creek Federally Qualified Rural Health Centers serving 21,000 West Virginians. Craig moved to West Virginia as a VISTA volunteer in the 1960s, observing no fast food and the coal miners had gardens. He and a team of clinicians soon learned from Dr. Eric Westman of Duke University about insulin resistance, carbohydrate intolerance, and the health benefits of removing sugar to prevent and reverse obesity and diabetes, and they came back and rethought how they practiced. This type of thinking and practicing medicine outside of the box, yet based on solid science, is necessary to end the pandemic of obesity in the Trans-Appalachian South and the rest of the world. Craig notes: [45]

Does the term epidemic mean that there is an exposure to a cause or to causes? We know about the virus causing COVID 19 and that spread and incidence is aggravated by certain social behaviors and contact. We know about the very fine coal dust causing coal workers pneumoconiosis (CWP) on an epidemic scale in the coalfields and the ongoing battles for the coal industry to pay the real cost of their coal production methods. We are learning more daily about how the prescribed opioids were allowed to create an epidemic and one of the dominant diseases of despair.

In the case of obesity and diabetes we appreciate that the conditions have been growing more and more prevalent over the past 40 years, but it is not clear to most people as to what the exposure and the cause is. This means that we tend to blame the victims for obesity and diabetes or just accept it as what happens in our family.

In the case of COVID, black lung, and the opiate addiction epidemics the responses to the diseases have taken on a strong political color with major interests trying to shape the public debate and in all three cases generating big Federal investments in treatment and prevention.

That hasn’t happened with obesity and diabetes even though these conditions cause more medical expenditure, more suffering and disability, and more deaths than the others [46].

In closing, I hope this essay makes the case that Appalachia need not be doomed with fatalism. Health care providers are giving hope. The best evidence to date implicates the main culprit as sugar along with processed junk foods but we have a lot to learn and unfortunately cannot do the magic wand experiment and reset modern life to one of generations past. I wish to thank all who have contributed the time, thoughts, research, insight, and especially hope to create this essay. Together let’s create a new chapter for obesity and diabetes in Appalachia.

Dr. Mark Cucuzzella, a Professor at West Virginia University School of Medicine is ig improving rural health in West Virginia by addressing social determinants of health through innovative metabolic medicine approaches, community-based interventions, and advocacy for low-carbohydrate nutrition, transforming patient care and medical education to combat the state’s high rates of diabetes and obesity

Article Reference: Appalachia – References