Cancer

Cancer & Metabolic Health: An Achilles’ Heel We Can No Longer Afford to Ignore

America the Sick

The United States is experiencing one of the most crippling healthcare crises in modern history. Approximately 90% of American adults are metabolically unhealthy, and fewer than 7% achieve optimal cardiometabolic health2. Metabolic dysfunction is pathologically linked to the development of nearly every major chronic disease facing Americans today, many of which are increasing at an alarming rate3,4. Among these conditions, cancer remains one of the most devastating, affecting both children and adults and placing significant strain not only on patients, but also on their families, surrounding communities, and the healthcare system at large7. In 2024 alone, more than 2 million Americans were expected to be diagnosed with cancer, including nearly 15,000 children and adolescents – globally positioning the U.S. among the top 10 countries with the highest cancer incidence rates8.

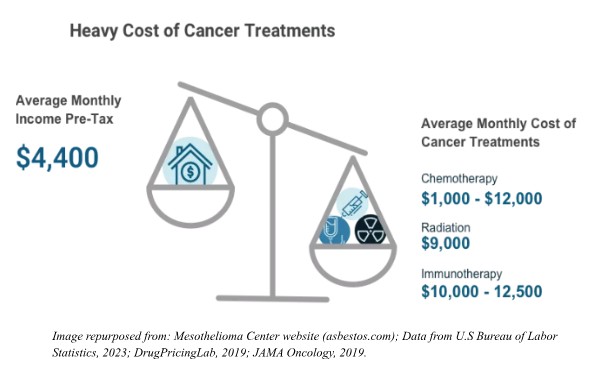

The state of cancer in the U.S. threatens the fundamental stability of our healthcare infrastructure which holds one of the highest economic burdens in the world. The cost of cancer care in the U.S. is estimated to reach 246 billion by 20309. Furthermore, cancer survivorship is accompanied by its own set of painful challenges due to side effects from its life-saving treatments. A longitudinal analysis of more than 14,000 childhood cancer survivors showed increased risk of late-onset complications and premature death10. By 50 years of age, half of the cohort had experienced a severe or disabling complication or had died, largely attributable to treatment-related effects. Cancer survivors not only face physiological and psychological challenges but also significant financial burden too – with 25% reporting financial hardship and difficulty paying medical bills11.

Stalled Progress

Five decades ago, President Nixon initiated the “War on Cancer” by signing the National Cancer Act of 1971, with a mission to improve outcomes and advance research. At the time, cancer was the second leading cause of death in the United States. Despite decades of research, trillions of dollars in funding, and significant technological advancements, cancer remains the second leading cause of death.

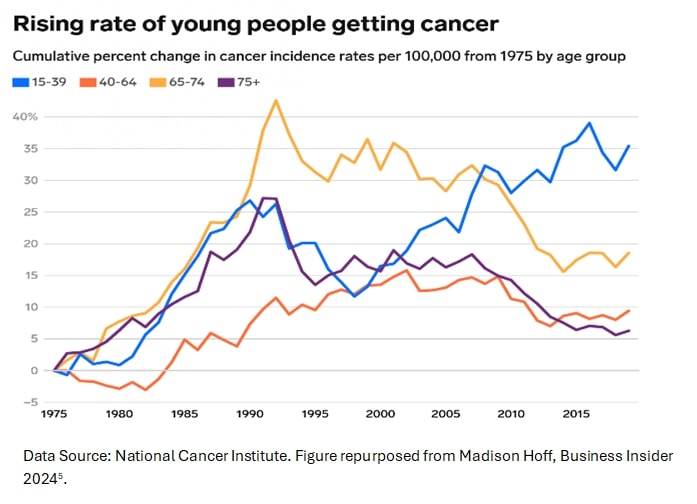

Of great concern, recent data indicate a rise in the incidence of “early-onset” cancers among adolescents and young adults, with gastrointestinal cancers in people under 50 increasing significantly12-14. Additionally, the prevalence of several types of common cancers – including breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancer – has also risen15-17.

Half a century after the National Cancer Act was established, cancer continues to have a deadly strong hold on Americans. Global projections suggest it will account for more than 15.3 million deaths annually4 by 2040 and soon become the leading cause of death in the United States18.

Deeper Than DNA

Despite improved early detection and treatment advances, stalled progress in addressing the U.S.’s cancer burden has experts questioning if research priorities need reevaluation. Cancer is a biologically complex and insidious disease and has traditionally been viewed primarily as a genetic disorder wherein spontaneous DNA mutations initiate and drive disease progression19; however, a rapidly growing wealth of data suggests that modifiable lifestyle factors including diet, physical activity, and environmental exposures result in metabolic dysfunction that may be equally or more important in cancer development and progression20. In fact, some research suggests that only 5-10% of cancers are primarily due to genetic defects, while the remaining 90-95% may be attributable to lifestyle and environment1.

Over the past few decades, the Standard American Diet (SAD) has become characterized by excess consumption of processed foods, refined grains, and added sugars which have reached an all-time high. Studies show that nearly 60% of calories in the average American adult’s diet come from ultra-processed foods (UPFs)21. Even more troubling, children and adolescents now consume nearly 70% of their calories from these foods21. UPFs have been associated with more than 32 health conditions, including cancer, and higher consumption has been linked to an increase in all-cause mortality22.

Acquisition of the SAD has been coupled with a switch to a sedentary lifestyle and increased exposure to environmental toxins such as BPA, PFAS, and microplastics, all of which are independently linked to both metabolic disease and cancer risk23-26.

Research indicates that this combination of lifestyle factors leads to metabolic disease and fosters a physiological environment conducive to cancer development. While not unexpected, this connection is under acknowledged in public health communications, which often overstate progress in combating cancer and frame cancer risk as largely attributable to random chance, despite evidence to the contrary. Interestingly, while systemic metabolic disorders such as obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia elevate cancer risk, dysfunctional metabolism within the cells of the tumor itself—a hallmark of the disease—drives its progression.

The Metabolic Face of Cancer

Over a century ago, scientists first discovered that cancers exhibit an abnormal metabolism characterized by excessive glucose consumption27. Today, researchers understand that the hallmark metabolic dysfunction observed in cancer cells provides energy, signaling intermediaries, and cellular building blocks required to support unbridled growth, suppress immune surveillance, and facilitate metastasis28. In fact, these metabolic features are considered fundamental to cancer initiation, progression, and survival29. Thus, metabolic dysfunction is now known to be both a cause and a consequence of cancer, representing an extremely promising therapeutic target for both cancer prevention and treatment30,31.

Over the last decade, drug-based approaches targeting cancer’s unique metabolic features have yielded novel and promising treatment strategies, but the field has continued to focus on designer pharmaceutical development against affected metabolic pathways32. Indeed, the majority of research in cancer metabolism has overlooked the most accessible and cost-effective lever we possess: reprogramming cellular metabolism through dietary, lifestyle, and environmental modifications.

Consider the ketogenic diet (KD), a high-fat, low-carbohydrate nutritional regimen that has been used clinically for over 100 years to treat refractory epilepsy33. Pre-clinical research dating back to the 1990s has demonstrated its anticancer effects in models of numerous cancer types, including some of the most common and aggressive (brain, colorectal, breast, prostate, lung, liver, gastric, pancreatic, thyroid, and more)34-52. Molecular research has elucidated that this metabolic therapy exerts therapeutic effects through multiple distinct yet simultaneous mechanisms52, including 1) suppression of glucose and insulin signaling53, 2) epigenetic modulation38 via HDACi and BHB-ylation38, 3) anti-inflammatory effects54, and 4) enhanced antitumor immunity39,44,55 through T-cell metabolic reprogramming56,57. Furthermore, research suggests that therapeutic ketosis sensitizes tumors to standard of care therapies including radiation42,58,59, chemotherapy42,43,59-63, and immunotherapy39,44,56,57; preserves muscle function and prevents cancer cachexia46-48,64-66, and improves quality of life measures in patients67. Consider the potential impact of such a broadly functioning therapy in contrast to pharmaceuticals that are designed to target a single genetic pathway, and which have been the primary focus of cancer research for the past several decades.

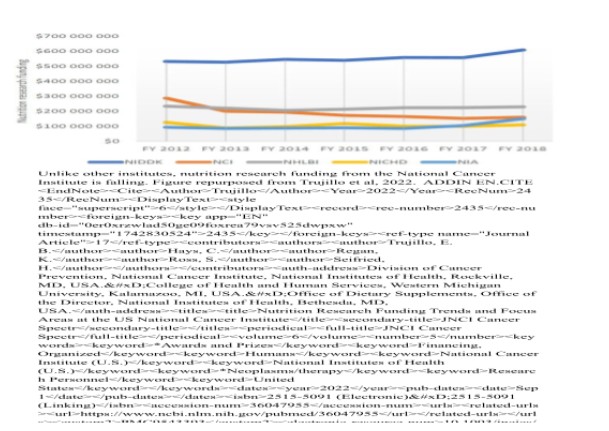

Despite strong scientific rationale and encouraging preliminary results, very limited funding has been awarded towards progressing early-stage research on ketogenic diet or other lifestyle-focused interventions for cancer into the human trials required to translate such findings into practice6. Notably, if a pharmaceutical intervention demonstrated even a fraction of the preclinical benefits reported in the scientific literature on ketogenic diet for cancer, substantial funding would have been readily allocated to assess its safety and efficacy in large-scale human trials. However, such trials remain lacking for ketogenic approaches, due simply to insufficient financial support for their completion.

Disparity in Funding

Funding disparity is a pervasive problem in oncology. Research on dietary or lifestyle-based interventions for cancer remains critically underfunded 6, a problem rooted in several systemic challenges. Implicit bias within the medical community often dismisses such strategies as “alternative” or insufficiently rigorous compared to pharmacologic approaches68, despite mechanistic evidence that suggests otherwise.

This is compounded by a longstanding research paradigm that prioritizes gene-centric drug development — an approach that aligns with traditional industry and academic incentives but neglects the host of metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer that are exploitable by diet and environmental factors69. Furthermore, oncologists receive minimal formal training in nutrition70, perpetuating a knowledge gap that undermines advocacy for diet trials. Together, these factors create a cycle in which underinvestment stifles high-quality evidence, reinforcing skepticism and hindering the integration of nutrition and other lifestyle-based interventions into mainstream oncology research and practice.

Over the past two decades, revenue generated from cancer drugs by some of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies has increased by 70%: from 55.8 billion to 95.1 billion71. While these profits have fueled advancements in cancer technology and treatments, the fight against cancer is far from over. Despite preliminary evidence suggesting nutritional and other lifestyle-based metabolic interventions can be both safe and efficacious, such interventions do not hold the same revenue-generating or ROI potential as pharmacological treatments and therefore do not receive meaningful attention or funding from private interests. Thus, the only way that lifestyle-focused cancer research will be supported is through philanthropic and public funding support. Publicly funded scientific research should prioritize the public good, ensuring taxpayer investments directly serve the people through accessible, equitable advancements rather than profit-driven outcomes.

Economic Benefit of Funding Metabolic Therapy

The discovery of an effective, low-cost dietary therapy to prevent, delay, or treat cancer would yield transformative benefits for the U.S. citizenry, government, and healthcare system.

By reducing reliance on expensive pharmaceuticals, radiation, and hospitalizations, such an intervention could dramatically lower the $200+ billion annual cost of cancer care, alleviating strain on Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers alike72. Even a 10% reduction in cancer burden due to lifestyle-based prevention would garner nearly $25 billion in annual savings. A proactive, prevention-focused approach would curb late-stage disease burden, freeing resources for other healthcare initiatives and reducing productivity losses caused by cancer morbidity and mortality. Additionally, widespread adoption of dietary strategies could mitigate health disparities, as accessible nutritional interventions could reach low-income and rural communities disproportionately impacted by cancer and for whom excessive healthcare costs often fall to state and federal governments. Long-term savings from reduced disability claims and a healthier workforce would bolster economic output while positioning the U.S. as a global leader in cost-effective, patient-centered oncology innovation. By prioritizing focus on safe and efficacious lifestyle-based interventions, such a breakthrough could reshape healthcare paradigms, prioritizing sustainability and equity in ways that benefit both public health and fiscal stability.

Call to Action – Metabolism is the Missing Piece to the Puzzle

Current standard of care strategies (surgery, genomics-targeted chemotherapies, radiation, immunotherapy) save lives but fail to address metabolic dysfunction in both tumors and patients, overlooking a primary driver of disease progression while compromising health and recovery. It is unlikely that major progress in the fight against cancer will be made without addressing the gap in knowledge, education, and research into lifestyle-based therapeutic strategies that target metabolism. It is time to ask if our lack of progress in the “War on Cancer” is due to a failure to address the fundamental issue of metabolic dysfunction in both cancer prevention and treatment.

Lifestyle-based metabolic therapies target core cancer mechanisms in a way that current treatments do not, and warrant exploration as a readily implementable, cost-saving therapeutic tool. However, to advance metabolic oncology, major changes will be required at the federal level – across research, funding, education, and policy. These changes include:

- Increasing federal funding earmarked for research on lifestyle-based metabolic therapies for cancer prevention and treatment, including precision nutrition.

- Reimbursing non-pharmacological interventions like metabolic therapy through healthcare policy reform.

- Incorporating evidence-based nutrition education into medical training and oncology guidelines.

- Updating dietary guidelines and launching educational campaigns to discourage consumption of cancer-linked processed foods, refined carbohydrates, and added sugars.

The time to act is now. The cost–in American lives and national resources–of ignoring evidence-based metabolic tools to prevent and treat cancer is no longer acceptable or sustainable.

Dr. Angela Poff, a researcher at the University of South Florida, is revolutionizing cancer treatment through her groundbreaking work on metabolic-based therapies, particularly exploring the potential of ketogenic diets and hyperbaric oxygen to exploit cancer metabolism and improve patient outcomes.

Victoria Field, co-founder of Metabolic Health Initiative and Metabolic Health Summit, is a force in championing evidence-based education on metabolic health and therapies, bringing together world-renowned experts to advance research and improve human performance across various health conditions.

Article Reference: Cancer – References