Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease

Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease: The science is not settled Brief Synopsis

Despite having received more funding than any other disease in history, cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be a leading and unabating cause of morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, in recent decades innovations in pharmacotherapy targeting LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels have led to a progressive lowering of total cholesterol and LDL-C; however, the burden of CVD on health and economics remains as strong as ever (Libby, 2021). The conclusion is clear: the eyes of our focus and thrusts of our efforts are misplaced.

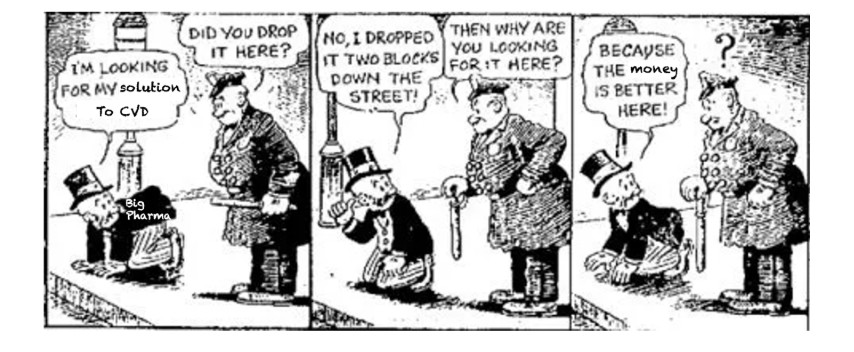

Like the proverbial man under a streetlamp, we are looking for solutions where there are profitable drugs to target biomarkers, rather than where we can most help prevent and treat the disease.

For example, in one of the largest population studies to date, high insulin resistance score (LPIR) was associated with a ~14-fold larger risk increase in new onset coronary heart disease than LDL-C (Dugani et al., 2021). So, why does the focus of discussion remain, primarily, LDL-C and the associated biomarker ApoB? Simple: We have profitable drugs that can easily lower LDL-C and ApoB. Otherwise stated: “Because the money is better here,” in the light of a clear, profitable business model. But to truly reduce insulin resistance and associated metabolic dysfunctions (afflicting >88% of Americans) requires lifestyle change.

Intermittent fasting, therapeutic carbohydrate restriction (low-carb), and ketogenic diets are among three dietary strategies that show high promise for improving metabolic health throughout our metabolically sick population. It’s time to look where there are the best solutions, not just where the light of profit shines brightest.

Further details

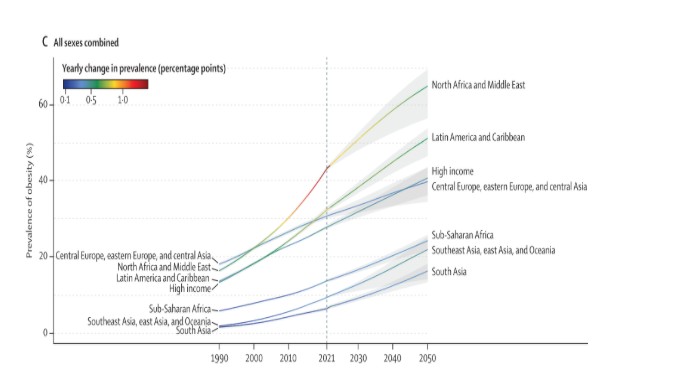

The health and economic impact of CVD and its risk factors cannot be overstated. Independent burden of disease analyses agree that CVD represents a major concern for all healthcare systems around the world (Hecker et al., 2022). Moreover, the most recent projections show this trend is not expected to change soon (Ng et al., 2025).

While it is undeniable that different ethnic groups have different cardiovascular risk profiles and that biological factors (i.e. biological sex, ethnicity, etc.) influence CVD susceptibility (McClelland et al., 2015), recent analyses have documented that mortality is much better explained by lifestyle (and therefore modifiable) factors (Argentieri et al., 2025; “Global Effect of Modifiable Risk Factors on Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality,” 2023).

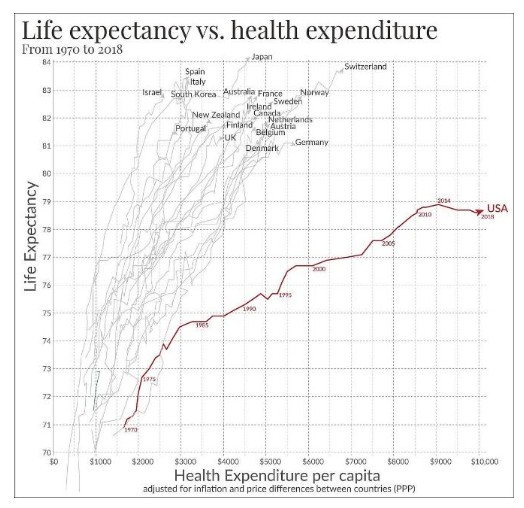

Despite having received more private and public funding than any other disease in history, CVD continues to be the leading cause of mortality and morbidity. The United States of America has the worst health-expenditure-to-life-expectancy ratio among developed countries. (As an epidemiological aside, the French – ‘despite’ their high intake of saturated fat – live ~5 years longer than Americans on average.)

Several independent reasons explain why cardiovascular disease continues to cause so much harm despite all the money and effort spent on developing treatments and policies to curtail it. Among them, we should highlight the following:

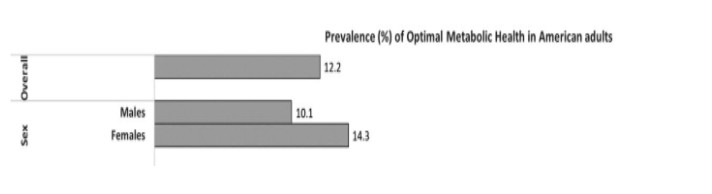

1. During the last decades, the number and the proportion of Americans with poor metabolic health has increased, and recent studies have shown that more than 88% of Americans present signs of insulin resistance (Araújo et al., 2019).

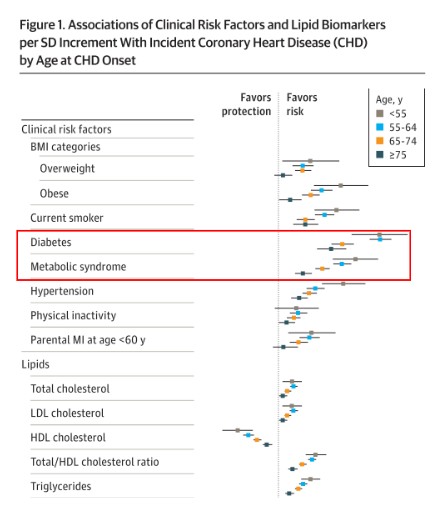

It is worth noting that, in head-to-head comparisons across age groups, insulin resistance (or metabolic syndrome) has a stronger link with CVD, than smoking, obesity, hypertension, sedentarism, dyslipidemia, or many other risk factors. Notably, it is the group of young adults in which this risk factor shows its largest magnitude (Mora et al., 2021). In other words, the economic impact of CVD on persons in their economically active years in the United States is likely larger than its impact on overall mortality. Thus, not only does CVD continue to kill, but mortality rate underestimates its true burden.

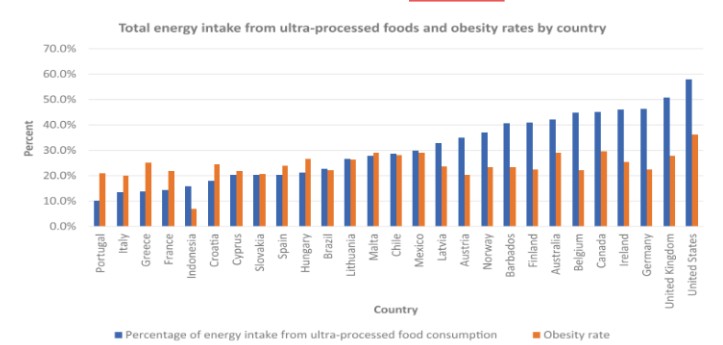

While insulin resistance is also the result of multiple simultaneous factors, the uptick in the consumption of ultra-processed foods, rich in sugar and refined carbohydrates, is a major driver. Notably, the United States is the largest consumer of ultra-processed food in the world (Crimarco et al., 2022).

Most of the available pharmacological treatments do not improve insulin resistance (statins, in fact, can worsen it and increase incidence of type 2 diabetes), but were primarily developed for reducing cholesterol. The few treatments that have documented cardiovascular risk reduction are associated with loss of excess weight (including GLP-1 receptor agonists), if prescribed for all eligible American citizens, would result in either an insurmountable financial burden (Wright et al., 2023).

Of note, similar results for weight loss can be achieved with multi-modal lifestyle therapy, but these yield economic savings, rather than economic burden (Buchanan et al., 2025).

Clinical tools for estimating CVD risk and guiding preventive interventions have been based on those risk factors that are modifiable by medications (like blood pressure and cholesterol) (Goff et al., 2014).

However, the Epidemiology and the Biomedical knowledge on the causes of CVD developed simultaneously with the increment in consumption of ultra-processed foods.

Does Cholesterol Matter in Healthy Americans?

Consequently, the independent influence of risk factors like LDL-C (and ApoB), has not been adequately studied in people without insulin resistance. In fact, never before have we properly assessed the risk associated with high LDL-C and ApoB in metabolically healthy, insulin sensitive persons without clear genetic dysfunctions, leaving a major “data hole” in the prevalent lipid-heart hypothesis. Thus, to potentially change the tide about how we see CVD, one strategy would be to plug this hole by answering the question using emerging populations newly under study.

For example, emerging evidence suggests that even people with extremely high blood LDL-C (and ApoB) may not have increased CVD in people without insulin resistance or inflammation or a genetic disorder in lipid metabolism

*Soto-Mota A.S. & Norwitz N.G., et al. in press, available April 7, 2025: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacadv.2025.101686.

*For early access and content breakdown, please contact adrian.sotom@incmnsz.mx and/or nwitz99@gmail.com

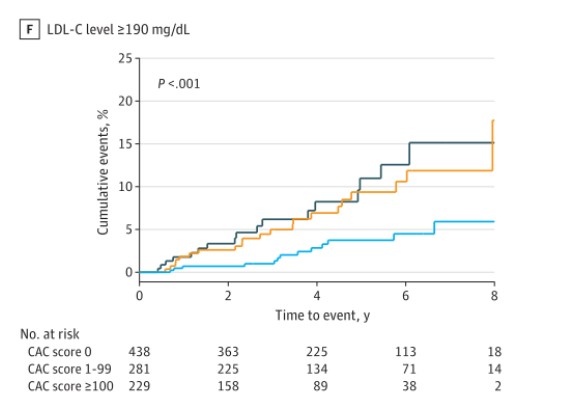

Importantly, recent studies have shown that cardiac imaging tools to measure Coronary Artery Calcium are more reliable for identifying those patients at risk (Budoff et al., 2023; Greenland et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2023; Mortensen et al., 2022; Nerlekar et al., 2025). Thus, although we have stronger risk factors, clear solutions to those risk factors, and better risk assessment tools, we remain stuck in the past – anchored by a prescription drug-based business model. To change the landscape of metabolic health and CVD, we need to acknowledge this reality and work to change norms throughout society and medicine by finding ways to invest in critical research (including on the aforementioned metabolically healthy populations[s] with very high LDL-C and ApoB) and collaboration to change out social and food ecosystems to improve population insulin resistance and metabolic health.

Dr. Adrian Soto-Mota, an MD and Ph.D. from Mexico and Oxford is a leading clinical researcher at the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Salvador Zubirán. Dr Soto Moto publishes extensively on metabolic health, nutrition interventions, and evidence-based medicine.

Dr. Nick Norwitz, a Harvard Medical School student and Oxford PhD, is the next generation metabolic medicine through groundbreaking research on ketogenic diets, lean mass hyper-responders, and the Lipid Energy Model, while advocating for personalized approaches to metabolic health based on his own transformative experience overcoming chronic illnesses

Article Reference: Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease – References