Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Next Steps for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Make Gastrointestinal Tracts Healthy Again

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, are debilitating disorders affecting ~3 million Americans and imparting a commensurate economic burden of ~$8.5 billion annually. The etiologies of inflammatory bowel diseases are poorly understood, including, and especially, environmental contributions imparted through our modern ultra-processed food ecosystem. For example, in a prospective assessment of 187,849 persons in the UK Biobank cohort, higher processed food intake was associated with a two-fold greater risk of developing Crohn’s disease, and among those with pre-existing IBDs, UPF intake was associated with a four-fold greater increased need for surgery.

In framing this discussion and the burden these diseases place on patients, it’s important not to lose sight of the direct effects as well as the indirect social and psychological knock-on effects. These diseases result in profound pain, uncontrollable and often unpredictable episodes of diarrhea—many times with blood—along with anemia and an increased risk of other chronic diseases secondary to systemic inflammation. Furthermore, the difficulties in navigating life often cause patients to withdraw socially, likely contributing to mental health disorders and depression, as well as decreased economic efficiency at both the individual and population levels. Thus, the $8.5 billion price tag on IBD care likely grossly underestimates the true economic burden due to lost workplace productivity. Consider what good could be served if a doctor suffering from severe ulcerative colitis could care for more patients or conduct more research with the months and years retrieved from the bowels of their disease. The same is true for business people, government employees, and so on.

While the pathophysiologies of IBDs are complex and poorly understood, there are almost certainly contributions from (i) genetics, (ii) gut and microbiome disruptors in our environment and the food supply, (iii) an autoimmune component, and (iv) a top-down neuropsychological component.

Among these factors, factor (ii), related to our food environment, is likely the most impactful and understudied. Like obesity, IBDs are largely a modern disease—an epidemic unveiled by the rise of a deluge of chemicals that have flooded into our food supply over the decades. And while we can easily find connections between the broad class of foods termed UPFs, dissecting exactly which components in the food supply are contributing to increased risk and worsened prognosis of these diseases is no easy feat. The carefully controlled studies needed to answer such questions are difficult to conduct and are easily confounded in human trials.

Animal model literature can afford some insights. For example, a study in IBD-prone mice identified that RED40, the most common food dye, with an annualized production of 2.3 million kg/year, can contribute to IBDs by altering levels and activity of an inflammatory molecule, IL-23. Of note, this molecule is also a target of immunosuppressant medications used in humans to treat IBDs, reinforcing the human relevance of these data.

It is easiest to envision the problem in terms of simple representative probabilities: Since long-term safety testing does not occur for most chemicals and additives introduced into our food supply (and our gastrointestinal systems), each carries some probability of contributing to IBDs, like RED40. Even if the chance that the aforementioned animal model findings translated to humans were only 10% (although it’s likely a much greater probability), what happens when you roll that 10-sided die 10,000 times? The result is what we see before us today.

This begs the question: What is the most impactful next step, in terms of policy and/or research priorities, to reduce the incidence of IBDs and improve disease course for patients? In my opinion, as a PhD researcher in human metabolism, healthcare provider, and an IBD patient in remission myself, the answer is clear: we need serious, rigorous, randomized controlled dietary trials for IBD treatment.

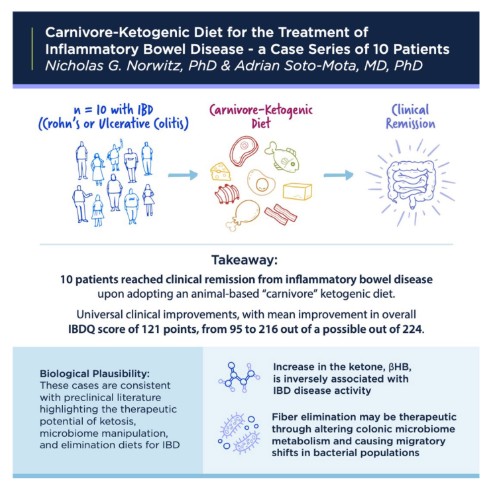

As an example, a six-month large-scale randomized trial comparing a whole-food, plant-based vegan diet versus a fully carnivore diet would afford tremendous insight and benefits to patients and the scientific community. There is, in fact, reason to believe that a carnivore diet could be tremendously beneficial for IBD patients. On first principles, the elimination nature of the diet and the anti-inflammatory properties of ketone bodies produced as a function of dietary carbohydrate restriction could eliminate disease triggers and reduce inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. In fact, in patients with IBDs, higher ketone levels are associated with lower disease activity. Furthermore, fiber elimination is already known to be therapeutic in Crohn’s disease, inducing remission in 60–85% of cases, possibly secondary to shifts in microbiome metabolism.

And, promisingly, in a recent 10-patient case series, a carnivore diet was successful at inducing clinical remission in all patients (Pictured)—some with decades-long histories of IBDs and complex pharmacological and surgical histories. Notably, all these patients are now in medication-free remission on a carnivore diet.

Supporting such trial(s)—which, candidly, is in design and could be run by associates of the Coalition for Metabolic Health and colleagues at Harvard and/or Stanford—would not only directly serve patients and the biomedical community and have the potential to reduce healthcare costs, but it would also serve as a clear and strong signal that diet is at the root of chronic modern disease. A dietary approach such as the carnivore diet—one that is diametrically opposed to the healthy Eating Guidelines and platitudes currently promoted to the public—could not only be acceptable but could itself be powerful medicine in a world sickened by a food supply filled with “bad energy.” In a battle between conventional ideas around eating and disruptive “extreme ideas” (e.g. ketogenic diet, carnivore diet, etc.), which would win as medicine? The answer could not only serve patients and science but also serve as a masterful strategic chess move inside a food politics ecosystem that is itself so confused one could diagnose it with delirium.

Dr. Nick Norwitz, a Harvard Medical School graduate and Oxford PhD, conducts groundbreaking research on ketogenic diets, lean mass hyper-responders, and the Lipid Energy Model, while advocating for personalized approaches to metabolic health based on his own transformative experience overcoming chronic illnesses.

Article Reference: Inflammatory Bowel Disease – References