Insulin Resistance and Gynecologic Disease

INSULIN RESISTANCE AND GYNECOLOGIC DISEASE

Insulin resistance is a critical and under-recognized risk factor for the development of obstetrical and gynecologic disease. Heavy or irregular menstrual cycles, uterine fibroids, female infertility, polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, and pregnancy complications are debilitating medical concerns that significantly impact quality of life, often leading to work absenteeism, reduced productivity, and increased utilization of healthcare resources. A focus on nutrition and reduction of high carbohydrate and ultra-processed foods can greatly reduce this disease burden.

Incidence

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is one of the most prevalent gynecologic conditions, affecting approximately 30% of women of reproductive age in the United States. 1 AUB includes gynecologic problems including polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), heavy menstrual cycles, uterine fibroids, female infertility, and uterine cancer. It is the leading cause of benign gynecologic consultations and incurs an estimated $34 billion in US healthcare costs annually.1,2 At least seventy percent of reproductive age women have uterine fibroids.1 The prevalence of AUB appears to be increasing, mirroring the rising trends in metabolic disorders such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.3 Despite the considerable disease burden, healthcare efforts largely emphasize diagnosis and medical and surgical treatment rather than prevention. Given the well-documented associations between cardiovascular disease risk factors—including obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus—and AUB, 4–7 it is imperative to explore the underlying metabolic disturbances, particularly insulin resistance, as a key driver of gynecologic pathology.

Disease Burden

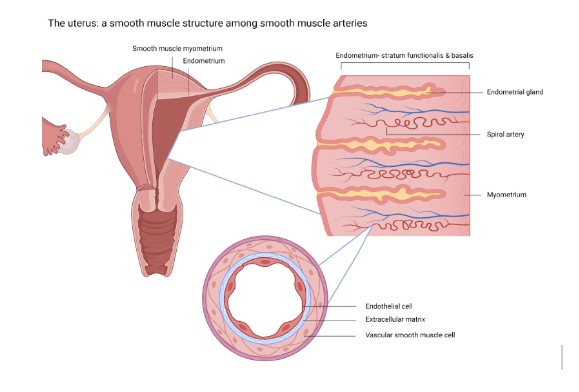

Heavy periods and AUB significantly impacts quality of life, often leading to work absenteeism, reduced productivity, and increased utilization of healthcare resources. 3 While the causes of AUB are multifaceted, growing evidence suggests a strong correlation between metabolic dysfunction and common gynecologic conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and endometrial polyps. 6–9 Several studies have drawn parallels between the pathophysiologic mechanisms of cardiovascular disease and the development of these conditions. For instance, research by Moss and Benditt (1975) demonstrated that progenitor myocytes in atherosclerotic plaques exhibit growth behaviors similar to uterine fibroids. 10 Additionally, Mesquita (2010) identified reactive oxidative species as key contributors to the development of uterine fibroids, akin to their role in atherosclerosis. 11 Furthermore, oxidative stress markers and angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, have been implicated in the formation of endometrial polyps. 12,13 Salcedo et al. (2025, in press) found hyperinsulinemia is associated with the most common forms of abnormal uterine bleeding. 14 The uterus shares structural similarities with peripheral arteries, as both are composed of smooth muscle tissue, which plays a critical role in their contractile function and vascular regulation. 15

As such, the uterus is susceptible to the same cardiovascular influences as blood vessels. Salcedo’s (2025, in press) findings suggest that the uterus may be subject to end organ damage stemming from systemic metabolic dysregulation, similar to the heart, kidneys, and other affected organs in cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

This metabolic connection with gynecologic health has serious negative implications on fertility and pregnancy as well. There are strong associations linking poor metabolic health to recurrent miscarriage, infertility, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, stillbirth, and maternal death 16–21.

Therapeutic Gaps

Despite the growing body of literature linking metabolic dysfunction to obstetric and gynecologic disease, clinical management remains largely focused on symptom control rather than addressing underlying metabolic drivers. One in three women will undergo hysterectomy in their lifetime.22 While the association between PCOS and insulin resistance is well recognized, 8,23 similar considerations are not consistently applied to other common causes of AUB, such as leiomyomas or heavy periods. Given that insulin resistance and dyslipidemia frequently precede the onset of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease,24,25 it is plausible that hyperinsulinemia may play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of benign gynecologic conditions. However, routine metabolic screening is not standard practice in gynecology, leaving a critical gap in early identification and intervention.

Emerging evidence supports the need for metabolic assessment in gynecologic patients. A study by Salcedo et al. (2022) demonstrated an increased prevalence of insulin resistance among women with AUB, suggesting that fasting insulin levels may serve as a valuable marker for both gynecologic and cardiometabolic risk.26 Recognizing the uterus as a potential site of end organ damage due to endothelial inflammation opens new avenues for prevention and targeted therapy. However, the lack of clinical guidelines incorporating metabolic screening in the management of gynecologic problems remains a major limitation in addressing the root cause of these conditions.

Safety and Feasibility

Given the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its association with gynecologic pathology, integrating metabolic screening into routine gynecologic practice is both feasible and beneficial. Fasting insulin measurement is a simple, cost-effective, and minimally invasive test that can provide valuable insights into a patient’s metabolic health. Identifying hyperinsulinemia early could allow for timely interventions, including lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic therapies such as metformin, and other insulin-sensitizing agents that have been shown to improve both reproductive and metabolic outcomes. In fact, several studies have demonstrated a well formulated low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diet can improve outcomes in fertility and lead to resolution of PCOS. 27–30 Furthermore, modest and significant reduction of debilitating endometriosis symptoms was noted when treatment focusing on restoring the gut microbiome as well as inclusion of prebiotics, probiotics, and omega 3 fatty acids. 31–35

Furthermore, the principles of cardiovascular disease prevention—such as dietary modifications, intentional inclusion of essential dietary nutrients, weight management, and physical activity—could be extended to the management of AUB and related conditions. Current treatment strategies for AUB, including hormonal therapies and surgical interventions, fail to address the underlying metabolic dysfunction. By incorporating metabolic management into gynecologic care, it may be possible to reduce the long-term burden of both reproductive and cardiometabolic disease.

Call to Action

The association between insulin resistance and common women’s health conditions, including infertility, pregnancy loss/complications, AUB/heavy menses, PCOS, fibroids, and endometriosis, warrants urgent attention from healthcare policymakers and practitioners. Could it be that the increased prevalence of these obstetric and gynecologic conditions coincide with the similar rise in obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes? Despite robust evidence linking metabolic dysfunction to these conditions, clinical practice has yet to incorporate comprehensive metabolic screening and intervention as standard care. Addressing this gap is critical to improving patient outcomes, reducing healthcare costs, and mitigating the growing burden of metabolic disease.

To achieve this, the Department of Health and Human Services should prioritize research funding and policy initiatives aimed at integrating metabolic assessments into gynecologic care. This includes developing guidelines for fasting insulin screening in women with AUB and other gynecologic conditions, expanding access to metabolic treatments, and promoting interdisciplinary collaboration between gynecologists, endocrinologists, and cardiologists. By shifting the focus from symptom management to disease prevention, it is possible to not only improve reproductive health but also reduce the broader impact of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease on women’s health.

In conclusion, insulin resistance is a major, yet underrecognized, contributor to gynecologic disease. The parallels between cardiovascular disease and conditions such as AUB, fibroids, and pregnancy complications highlight the need for a paradigm shift in clinical care. By acknowledging the uterus as a potential site of end organ damage and implementing metabolic screening as a standard practice, healthcare providers can take proactive steps to address the root causes of these conditions. The time for action is now, and a collaborative effort is needed to ensure that metabolic health becomes an integral part of gynecologic care.

Dr. Andrea Salcedo, an Obstetrics and Gynecology physician at Loma Linda University, is a champion for women’s health by exploring the intricate connections between metabolic dysfunction, insulin resistance, and gynecologic disorders such as endometriosis, advocating for a root-cause approach to treatment and patient care.

Article Reference: Insulin Resistance and Gynecologic Disease – References