Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)

Introduction

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD), formerly known as Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in the world. This affects 25-30% of the world’s population, including over 80 million people in our nation. (1-5) Though there are reports dating to the 1800’s, it was 1962 when “hepatitis of the fatty liver” was described, (6) 1980 when the term Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) was introduced. (7) and 1986 when the term “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease” was first introduced. (8) It was initially believed this was a benign condition, but in the 1990s it was recognized that NASH was itself a serious disease with associated morbidity and mortality. In this short span of time, in parallel with the epidemics of obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome, cirrhosis due to this disease has become the leading indication for liver transplantation in women and those >65 years of age, and is on par with alcohol as the leading indication overall (9-11).

What Is It?

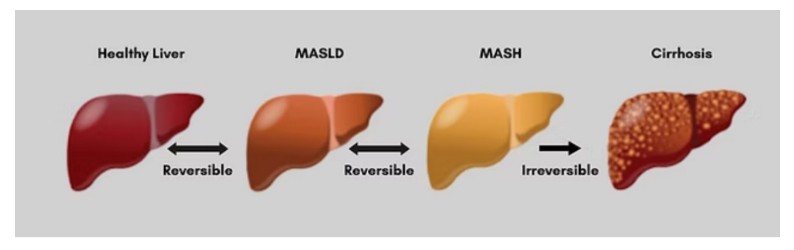

MASLD is defined by fat in the liver affecting at least 5% of the liver cells, after other causes of liver fat have been ruled out. MASLD can be divided into subtypes that range from simple fat in the liver to a more advanced disease known as Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Steatohepatitis or MASH, where this is not only fat in the liver cells, but also liver cell damage and liver inflammation. This damage and inflammation can lead to scarring and eventual cirrhosis of the liver with liver failure.

The recent name change to MASLD (99) reflects the fact that this condition is tied to metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. Insulin resistance is nearly universal in MASLD in the liver, adipose cells, and muscle. It is found at higher rates in patients. with components of metabolic syndrome (type 2 diabetes-78%, hypertension, high triglycerides, low HDL and central obesity-90% in the severely obese). (10-12)

MASLD, as with metabolic syndrome, should be considered part of a systemic disease process that includes risk for cardiovascular disease, now the leading cause of death in these patients, type two diabetes, hypertension, obesity, chronic kidney disease and obstructive sleep apnea. (12-83) People with MASLD and metabolic syndrome have a higher overall mortality rate, increased cirrhosis and liver related deaths, and higher rates of liver cancer. (4, 84) Non-liver cancer deaths (especially gastrointestinal cancers such as esophagus, stomach, pancreas, and colon, but also breast and gynecologic cancers) are among the top three causes of death in the MASLD population.(85 86)

The Scope of the Problem/Disease Burden

From the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) 2023 Practice Guidelines(87): the prevalence of NAFLD and NASH is rising worldwide in parallel with increases in the prevalence of obesity and metabolic comorbid disease (insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, central obesity, and hypertension). The prevalence of NASH/MASH in the general population is challenging to determine with certainty; however, the more advanced form-NASH/MASH was identified in 14% of asymptomatic patients undergoing colon cancer screening. (88) This study also highlights that since the publication of a prior prospective prevalence study, the prevalence of clinically significant fibrosis (stage 2 or higher fibrosis) has increased >2-fold. This is supported by the projected rise in NAFLD prevalence by 2030, when patients with advanced hepatic fibrosis, defined as bridging fibrosis (F3) or compensated cirrhosis (F4), will increase disproportionately, mirroring the projected doubling of NASH. As such, the incidence of hepatic decompensation, HCC (liver cancer), and death related to NASH cirrhosis are likewise expected to increase 2- to 3-fold by 2030. (89) In 2020 nearly 33.7% of US adults (close to 86 million) were affected by MASLD. 5.8% of US adults (14.9 million) were affected by MASH, (with 6.7 million affected by MASH with significant fibrosis).

In a simulation model (90), by 2050, the number of adult MASLD cases will increase from 33.7% to 41.4% close to 121.9 million adults! Cases of MASH would increase from 14.9 million (5.8% of US adults) to 23.2 million (7.9% of US adults). Cases of MASH with advanced fibrosis would increase from 6.7 to 11.7 million. Cases of liver cancer would rise from 11,483 to 22,440 cases per year. Cases of liver transplant would increase from 1,717 to 6720 per year. Liver related mortality would increase from 30,500 deaths (1.0% of all cause deaths in adults) to 95,300 deaths (2.4%) MASLD can also be seen in 4.1% of the lean population again, associated with metabolic comorbidities and visceral adiposity. Another special population, pregnant women, were found to have hepatic steatosis in 14%, rising to 20% in women with a BMI of 30 or greater. This is associated with increased complications including preterm birth, postpartum bleeding and hypertensive complications. These should be considered high risk pregnancies. (104)

This predicted crisis of burden of disease is coupled with predictions of physician shortages. In 2023 AMA President Jesse Ehrenfeld MD described it as an urgent crisis with a projected shortfall of 86,000 physicians by 2036. Beyond that, are medical schools training future physicians in the prevention and management of these chronic diseases? Who will be able to care for these patients?

Financial Burden

In his report, Burden of illness and economic impact of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in the United States (91) according to the prevalence of obesity, Dr. Zobair Younossi estimates costs for NASH to be $175 billion over the next 2 decades. This estimate does not include the costs of the newly approved drugs for MASH with fibrosis. This is a call to action to providers, payers, policy makers and other stakeholders to address this growing crisis and allocate resources to address the disease more aggressively, as well as allocate resources to implement appropriate preventive measures.

How Do You Get a Fatty Liver?

MASLD has multiple metabolic and genetic factors contributing to its progression. Gut dysbiosis and sedentary behavior also contribute. However, there are important pathways leading to accumulation of liver fat, (92-98) all involving excess carbohydrates (sugar and starches) above a person’s tolerance, a driver of insulin resistance:

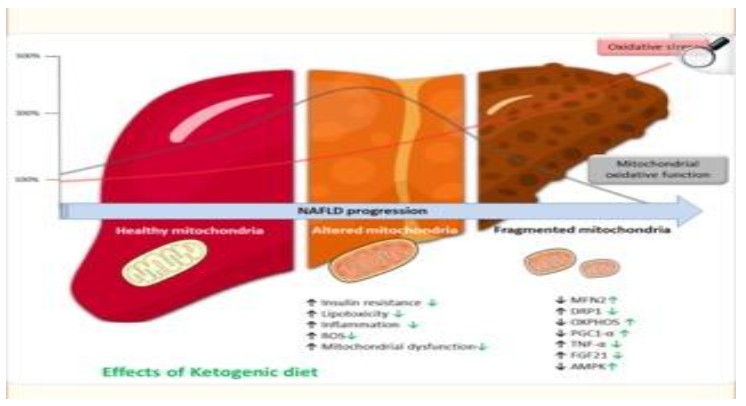

- The fructose molecule in sugar is considered a leading driver of metabolic syndrome and MASLD. Never before in human history have we seen this level of fructose consumption. Fructose in excess is a toxin to the mitochondria (the powerhouse and driver of energy) in the liver cells. A damaged mitochondria reduces the cells’ ability to produce energy and burn fat, promoting more fat build up in the liver cell and a reduction in energy production in the cells. Fructose increases fat building in the liver (de novo lipogenesis). Fructose can also be produced in the body during periods of eating excess carbohydrates, through a process called the polyol pathway.

- Excessive carbohydrates lead to elevated insulin levels, both of which promote fat building in the liver- de novo lipogenesis.

- Elevated insulin levels (brought about by excessive carbohydrate intake) also lead to growth of peripheral fat cells. As these cells become larger and insulin resistant, they begin to leak out their fat in the form of free fatty acids that travel throughout the body (ectopic fat) including to the liver, further promoting fat building in the liver.

MASLD in Children: A Crisis Unfolding

The rates of obesity in children have tripled since the 1960’s from 5% to 19.7%. This increase is occurring in all age groups, but especially in adolescents where it is estimated at 20.6%.(100) This correlates with an increase in other comorbidities including hypertension, pre- and type two diabetes, and MASLD. This increase is multifaceted with a range of factors including environmental/food availability, genetics, epigenetics, societal, financial, psychological and endocrinological influences. In addition to obesity and waist circumference, other factors play a role including age, sex, race and ethnicity. Adolescents, males, Mexican-Americans, those with high waist circumference and BMI > than the 85% percentile are at greater risk to have MASLD.(101-103)

Incidence in children

In the general pediatric population, the estimated prevalence of MASLD is 5-11%. In the obese pediatric population this estimate increases to 30-50%. In children with MASLD, reports vary with estimates of MASH (steatohepatitis) from 23-84%. (101-103) MASLD is even reported in newborns.

In one study, 33 stillborn infants of mothers with diabetes were compared to 48 controls. There was a significant difference in hepatic steatosis: 78.8% in the case group versus 16.7% in controls (P < .001). The severity was also greater in the case group. The authors conclude that there is a significant positive association between fetal hepatic steatosis and maternal diabetes. (105). This sets a child up for a lifetime of illness and early mortality through no fault of their own.

Long Term Outcomes

There are only a few long-term natural history studies on pediatric MASLD. A Swedish cohort study spanning 1966-2017 followed 718 pediatric and young adult patients with NAFLD confirmed by biopsy. These young patients saw higher risks for cancer-, liver-, and cardiometabolic mortality compared to matched controls. (106) Another study showed that with standard of care lifestyle advice, one third of children with MASLD showed progression of the disease in just 2 years. (107) Indeed, according to the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) database, of all transplants performed in adolescents and young adults between 2015 and 2020, 7% were for the indication of MASH/Cryptogenic cirrhosis.(108)

Gaps in Care

In Xanthakos’ 2020 study, (107) he documented that with standard of care lifestyle advice every three months, one third of children with MASLD showed progression of the disease in just 2 years, highlighting the insufficiency of this approach. This begs the question-are we giving the wrong advice? From a nutritional standpoint, other than avoidance of sugar sweetened beverages and weight loss, standard of care in guidelines remains: NASPGHAN (109)-“consumption of a healthy well balanced diet,” and AASLD-(87) “Although the benefits of the Mediterranean diet over other dietary approaches in small randomized trials is debated, it is sustainable and has cardiovascular benefits”. Other miscellaneous sources recommend against saturated fat, and to minimize red meat and animal- based proteins, toward more plant- based proteins, without the rigorous science to support this. (There is no approved medication for the pediatric population and this report will not discuss bariatric surgery, though references are provided.) This contrasts with a large body of evidence (110-127) supporting the consideration of low-carbohydrate diets, and especially ketogenic diets in the treatment not only of MASLD, (some showing quite rapid improvement), but also in the reversal of type two diabetes, metabolic syndrome and improvement of obesity, all linked to MASLD. Paoli and Cerullo’s review, (128) found that a ketogenic diet inducing “physiological ketosis” stimulated the activation of several key factors involved in liver-protective activities that alleviated oxidative stress and damage, improved the inflammatory response and restored mitochondrial function, globally improving liver function. More research in this area is needed.

Finally, many MASLD patients are lean or non-obese and these patients have not been studied well.

A Call to Action

First we must develop a governmental campaign to educate the public and health care providers (HCPs) about this disease, its link to insulin resistance, and its dangers, including risks of cirrhosis, multiple cancers, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, perinatal complications, early mortality and need for liver transplantation. We need a massive educational campaign about the role of fructose in sugar, and excess carbohydrates above a person’s tolerance and their contribution to insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and MASLD.

Second, we must have our nation undergo routine screening, as we do for other diseases. The public and HCPs must be educated on who and how to screen. The clinical practice guidelines from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN), as well as guidelines from the AASLD, AGA and other specialty organizations offer recommendations for screening in both the pediatric and adult population. HCPs must understand non-invasive testing (NITs) and non-invasive liver disease assessment (NILDA) including blood work and imaging studies/liver scanning to directly measure fat in the liver and assess the degree of scarring by a method called elastography.(87, 109) (It is of the utmost importance for primary care providers to identify patients with advanced fibrosis (scarring) who should be referred to a specialist, due to their higher rate of liver-related mortality and their eligibility for newly approved drug therapy (Resmetirom and Semaglutide in adults). (129, 130)

Primary care providers must also be trained to care for patients with less severe MASLD due to the shortage of specialists and estimates of the increasing number of patients with this disease.

Third, as outlined above, there is a tremendous financial burden on our nation from this disease. This is a call to action to providers, payers, policy makers and other stakeholders to address this growing crisis and allocate resources to address the disease more aggressively, as well as allocate resources to implement appropriate preventive measures.

- Finally, while there are many factors contributing to this disease, it is primarily driven by poor nutrition. There are many nutritional patterns recommended (Mediterranean, low fat, plant -based, calorie restricted, low-carbohydrate). Funding is needed to perform rigorous scientific studies to compare these patterns to nutritional ketosis given the studies done to date showing its benefit, not just with all features of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance, but with intrinsic liver health as well (128).

Dr. Karen Jerome-Zapadka, a board-certified gastroenterologist and obesity medicine specialist, is transforming metabolic health and combating fatty liver disease through innovative therapeutic carbohydrate reduction programs through her comprehensive obesity program, leadership in multidisciplinary nutrition committees, and tireless advocacy for patient education and awareness.

Article Reference: Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease – References