Gestational Diabetes

GESTATIONAL DIABETES: Rethinking Nutritional Guidelines for Maternal and Fetal Health

INCIDENCE

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common pregnancy complication, characterized by glucose intolerance first diagnosed during pregnancy. It affects an estimated 14% of pregnancies globally, with wide variability depending on diagnostic criteria and population health status.[1] Rates are rising globally in tandem with the population-wide increase in obesity and type 2 diabetes.[2] Data from the CDC indicates disparities in this diagnosis, specifically how it affects women of ethnic minorities and older women at higher rates.

A 2024 review article published in The Lancet notes that “Gestational diabetes direct costs are $1·6 billion in the USA alone, largely due to complications including hypertensive disorders, preterm delivery, and neonatal metabolic and respiratory consequences.”

Importantly, many cases of gestational diabetes are actually prediabetes or undiagnosed type 2 diabetes that were not diagnosed in advance of conception. This is why the California Diabetes and Pregnancy Program: Sweet Success (CDAPP) — one of the most comprehensive GDM care models — advocates for early screening of at-risk women using hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in the first trimester (as opposed to delaying screening until the conventional 24–28 weeks).[3] This allows for earlier intervention and improved outcomes. In women with a high first-trimester A1c, the likelihood of “failing” a glucose tolerance test later in pregnancy is over 98%.[4] According to CDAPP guidelines, an A1c of 5.7% or higher is considered diagnostic for gestational diabetes, allowing for early intervention to support optimal blood sugar control from the start.

DISEASE BURDEN & IMPACTS ON MOTHER AND CHILD

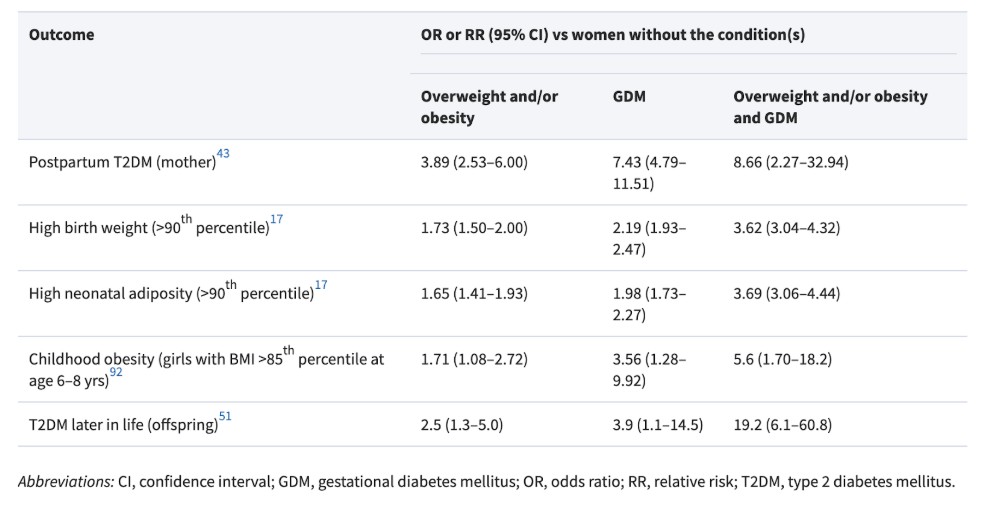

GDM is associated with significant short- and long-term risks to both mother and baby:

- Maternal risks: Preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, increased future risk of type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

- Fetal/neonatal risks: Macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, neonatal hypoglycemia, stillbirth, respiratory distress syndrome, and long-term risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Infants exposed to uncontrolled maternal blood sugar levels in utero face consequences of “fetal programming” in which their pancreas adapts by producing excessive amounts of insulin. This drives fetal overgrowth (macrosomia), but also permanently programs their metabolism for metabolic dysfunction and diabetes later in life. The chances of having a large baby correlate very strongly to blood sugar control during pregnancy. These children face upwards of a 19-fold increased risk of developing diabetes in their lifetime compared to children born to mothers with normal blood sugar levels (see table below).[5]

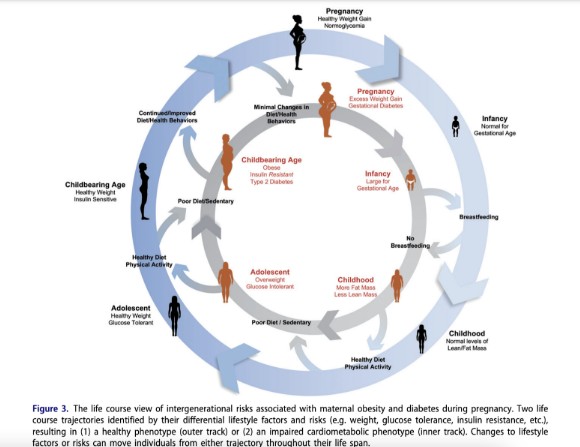

The following image shows how maternal health directly impacts intergenerational health and risk of disease.[6]

Standard approaches to GDM management focus on glycemic targets but frequently fall short in addressing the root cause: excessive glucose exposure, largely worsened by conventional high-carbohydrate dietary patterns.

CURRENT DIETARY GUIDELINES PREVENT OPTIMAL GLYCEMIC CONTROL

Despite improved diagnostics and growing awareness, major gaps remain in nutritional management.

Carbohydrate Guidelines & Ketones

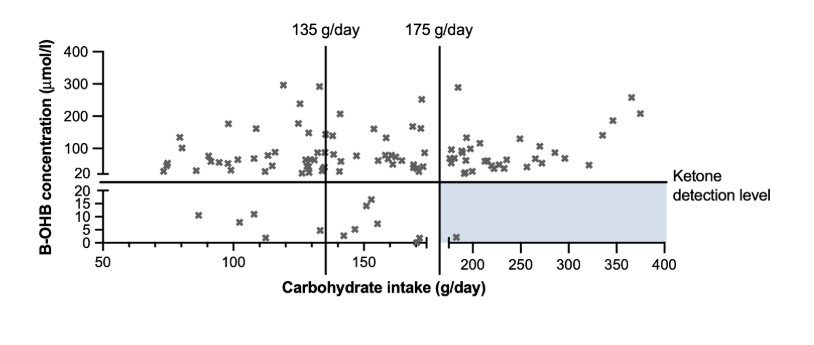

Conventional dietary recommendations—such as the advised minimum 175 grams of carbohydrates per day—are not evidence-based. These guidelines often lead to excessive postprandial glucose excursions, undermining metabolic control and increasing medication reliance. These recommendations are perpetuated due to unsubstantiated fears about maternal ketosis. A 2021 review in Diabetes Care critically evaluated the evidence supporting carbohydrate minimums and the avoidance of ketones in pregnancy [7]. It concluded: “While it is difficult to draw strong conclusions on the safety of ketones and carbohydrate restriction in pregnancy, we believe that there is insufficient evidence to support current recommendations on necessary carbohydrate intake and avoidance of ketones. We propose that current recommendations for pregnant women to consume a minimum of 175 g carbohydrate per day and to consume a diet that does not result in ketones be reviewed. There is insufficient evidence to support either of these recommendations, and they have the potential to limit the ability of women with DIP to restrict their carbohydrate intake in an effort to control blood glucose levels. In addition, given the high prevalence of maternal ketones, these recommendations have the potential to cause unnecessary anxiety among pregnant women.” There is no conclusive evidence that mild ketones pose harm to the fetus in eucaloric states; moreover mild ketosis is common throughout pregnancy as a natural consequence of changes to metabolism. There is also no clear connection between maternal carbohydrate intake and ketone levels (see image below).[8] Therefore, guidelines which prevent women from decreasing carbohydrate intake to their own personal tolerance levels are not only scientifically unfounded but may also hinder effective blood sugar management, unnecessarily increase dependence on pharmacologic interventions, and contribute to confusion and anxiety around normal metabolic adaptations in pregnancy. Low-carb diets in pregnancy have long been viewed with suspicion, largely extrapolated from poorly controlled diabetes (e.g., diabetic ketoacidosis) rather than physiological ketosis.

Protein Guidelines

The recommended protein levels for pregnancy are set 73% lower than true requirements (according to the first ever study to directly estimate gestational stage–specific protein requirements in healthy pregnant women), and yet our guidelines have not been updated since this new research became available in 2015.[9] Importantly, protein is critical for glycemic control, it promotes satiety, and protein-rich foods are some of the most concentrated sources of key micronutrients. Unfortunately, average protein intake of U.S. pregnant women is below this optimal level in 40% of 2nd trimester mothers, 67% of 3rd trimester mothers.[10]

IMPROVED OUTCOMES THROUGH NUTRITION

A 2019 systematic review of medical nutrition therapy for gestational diabetes published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics acknowledged “substantial limitations in MNT guidelines for patients with GDM”, including low rigor of recommendation development, lacking multidisciplinary input, low applicability, inadequate editorial independence (many conflicts of interest).[11] A growing body of evidence—including the work of Lily Nichols, RDN, CDE, author of Real Food for Gestational Diabetes—demonstrates the safety and efficacy of lower-carbohydrate, real food-based diets in managing GDM. The Czech Republic updated their nationwide gestational diabetes nutrition guidelines to reflect Nichols’ work, implementing a maximum recommended carbohydrate level in place of their previous minimum carbohydrate level and have since reported dramatic improvements in pregnancy outcomes, including less need for insulin, fewer maternal complications, and fewer adverse fetal outcomes (such as macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycemia).

Of note, dietary patterns that emphasize low-glycemic foods — protein-rich foods, non-starchy vegetables, low-sugar fruits, healthy fat, etc. — have the most abundant data and clinical efficacy for gestational diabetes management:

- Low-glycemic diets may reduce the chances that a woman with GDM requires insulin therapy by 50%.7

- Low-glycemic diets also reduce glycemic variability in pregnancy by approximately 50% (fewer spikes and crashes in blood sugar).[12] This is vital because higher glycemic variability, even of a modest degree, has been linked to higher fetal ponderal index (heavier weight relative to their length, usually indicative of excess body fat accrual in utero), independently of A1c. A meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials on low glycemic index diets found that this way of eating is associated with a significantly decreased risk of macrosomia.[13]

- Low-glycemic diets attenuate the severity of insulin resistance experienced in late pregnancy.[14]

- A meta-analysis of 11 trials involving 1,985 pregnant women found that a low-glycemic diet significantly reduced fasting glucose, 2-hour postprandial glucose, and the incidence of large-for-gestational-age (LGA) infants. While reductions in gestational weight gain and birth weight were also observed, these findings did not reach statistical significance.[15]

We are currently in a nutritional crisis nationwide, with 58% of the calories consumed by the average American coming from ultra-processed foods.[16] These refined carbohydrates drive blood sugar and insulin dysregulation.

CALL TO ACTION

GDM is not just a transient pregnancy complication—it’s an early marker of metabolic dysfunction that has lifelong implications for both mother and child. Addressing it effectively means revisiting current dietary guidelines:

- Reevaluate carbohydrate minimums in light of emerging evidence showing no harm—and potential benefit—of lower intakes. Clients should be made aware that they can safely “eat to the meter,” meaning they have permission to adjust their dietary carbohydrate intake to a level that prevents large blood sugar spikes after meals.

- Update protein recommendations to reflect new research. It is nearly impossible to achieve glycemic targets and meet the micronutrient requirements in pregnancy without substantially increasing protein recommendations.

- Incorporate early screening tools, such as HbA1c in the first trimester, into standard prenatal protocols for high-risk populations.

- Empower women with real food nutrition education that prioritizes glycemic stability, nutrient density, and metabolic health over adherence to outdated, carbohydrate-heavy guidelines.

- Support research into individualized nutrition therapy and maternal ketosis during pregnancy.

It is no longer adequate to accept suboptimal glycemic control and rising GDM rates as inevitable. With evidence mounting and clinical outcomes at stake, the time has come to align dietary recommendations for gestational diabetes with modern research—not outdated guidelines. Achieving optimal glycemic control during pregnancy could change the trajectory of maternal and infant health for generations to come.

Lily Nichols, RDN, CDE, a researcher and bestselling author of Real Food for Pregnancy and Real Food for Gestational Diabetes, has reshaped prenatal nutrition by challenging outdated guidelines and advocating for evidence-based, real food approaches that optimize metabolic health for both mothers and babies.