Gestational Diabetes

CHRONIC DISEASE AFFECTING MOTHERS and BABIES: Gestational Diabetes

INCIDENCE:

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is diabetes that is diagnosed during pregnancy, typically at the start of the third trimester. GDM emerges due to the diabetes-inducing hormonal state of late pregnancy, in addition to the mother’s underlying metabolic health. As the rates of obesity and other diseases related to insulin resistance have increased in the US population, so has the incidence of gestational diabetes. Over a recent five-year stretch, there was a 33% increase in the incidence of GDM in the US, from 6% to more than 8% (MMWR). Canada has seen a similar rise in the incidence of GDM, with rates doubling over the 14 years from 1996 to 2010 (Feig 2014). The median prevalence of GDM in North America is higher than in Europe (Zhu, Eades).

DISEASE BURDEN:

GDM is a window into the metabolic health of reproductive aged women as well as their offspring, and the picture is alarming. The health implications for both mother and offspring of GDM pregnancies are profound, as both the host and the inhabitant of a hostile uterine environment characterized by supraphysiologic glucose levels are at risk for poor outcomes. GDM-related complications drive up care costs, and adversely impact maternal and child health in the peripartum period:

- Increased rates of preterm delivery and stillbirth (Rosenstein),

- Increased risk of major congenital malformations (Kinnunen, Balsells, Zhao- RR, Wu, Schraw)

- Increased risk of chromosomal abnormalities (Kinnunen, Moore)

- Birth injuries related to fetal macrosomia (large size of the baby) which can cause permanent damage to babies’ arms, and fetal asphyxiation (Shoulder Dystocia reference)

- Need for neonatal intensive care unit admission

- Need for cesarean section

- Pre-eclampsia, a life-threatening condition for the mother

Significant health risks extend far past the delivery and neonatal period. Exposure to GDM in utero is associated with long-lasting health consequences:

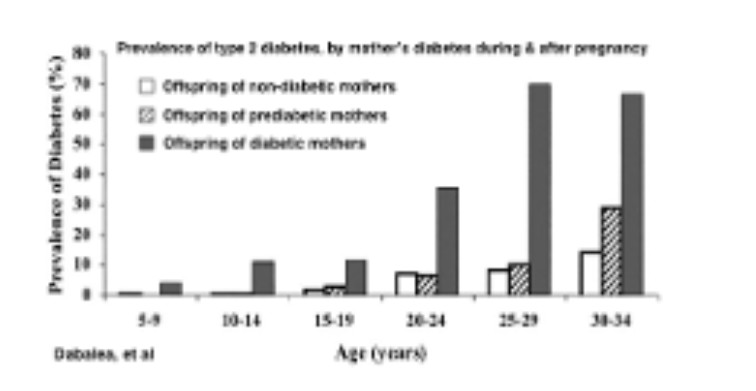

- People born to mothers with diabetes have an increased risk for childhood and young adult-onset of metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes, and early onset puberty in females (Dabalea, Blotsky, Grunnet, Perng- Diabetologia, HAPOFeig31)

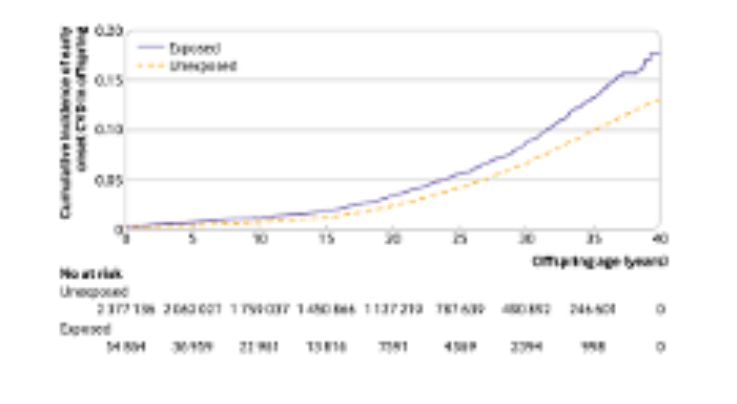

- Similarly, the offspring have increased risk of cardiovascular diseases (Perng, Sundholm, Yu, Feig)

- There is an increased risk for fatty liver disease in both mothers (50% increased risk) and offspring (2-fold increased risk) (Foo)

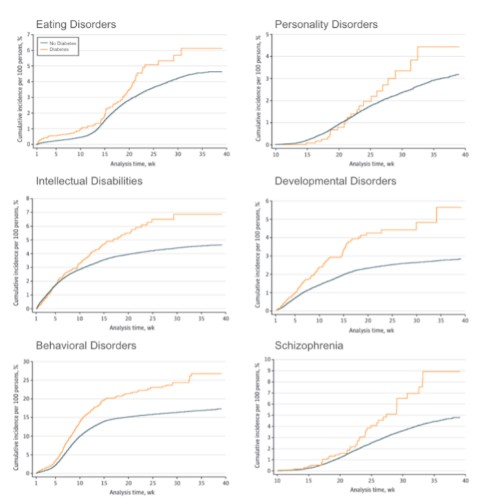

- Offspring of GDM pregnancies suffer from increased incidence of major psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia (Van Lieshout), anxiety disorders, eating disorders, personality disorders, developmental disorders, behavioral disorders (Silva), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, learning disorders, and autism spectrum disorders (Rodolaki, Xiang 2015)

- And have reduced cognitive and psychomotor abilities (Silva, Robles) compared to the offspring of unaffected pregnancies.

- Women with GDM have a 50% chance of developing type 2 diabetes within 10 years, which is far greater than the rate in women whose pregnancies were not affected by GDM.

While epidemiologic studies in humans find highly concerning associations between gestational diabetes and health outcomes, they cannot determine causation. However, animal models of maternal diabetes replicate the human findings using experimental manipulations, which confirms a causal role of gestational diabetes for the cardiometabolic (Grzęda, Hribar, Mihailovicova) and neurological, psychological, and behavioral abnormalities in offspring (Wang, Aviel-Shekler).

Thus gestational diabetes is part of a vicious intergenerational cycle that threatens the physical and mental health of Americans for decades and centuries to come. Breaking this pattern of ever-worsening metabolic health through improved nutrition aimed at all parts of the human life cycle, and with a particular focus on providing the healthiest pre-birth metabolic environments, will mark a powerful and meaningful shift in the trajectory of the health status of Americans.

THERAPEUTIC GAPS

Management of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) centers on achieving tight glycemic control to reduce maternal and neonatal complications (Maresh, Cyganek, Dabelea 2000). Given the unique physiology of pregnancy, blood glucose targets are lower than for non-pregnant individuals (ADA Standards of Care 2025). First-line treatment is dietary intervention, with insulin introduced if targets are not met. Even when carbohydrate intake has the greatest impact on glycemic control in pregnancy (Asbjornsdottir, Hill), yet current guidelines recommend a minimum of 175 grams per day (ADA), including high-carb foods like fruits, legumes, and whole grains. Despite increasing GDM prevalence and rising rates of cardiometabolic and neuropsychiatric conditions potentially linked to in utero hyperglycemia, the recommendation to consume ≥175 grams per day has not been rigorously examined.

Some studies, like Hernandez et al. (2014), suggest that higher (60% of calories) and lower (40%) carbohydrate diets yield similar average glucose levels. However, the 60% group had significantly higher glucose excursions, revealing a dose-response relationship between carb intake and glycemia—even within target thresholds—associated with adverse outcomes (Xiang 2015, 2018; Lowe 2019; Cyganek, Maresh). Despite this, no research explores the effects of reducing carbohydrate intake below 175 grams per day for pregnant women. This represents a critical gap, especially given that very low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets are the only dietary approaches shown to reverse or even remit type 2 diabetes, lower insulin resistance, reduce inflammation and blood pressure, and decrease medication dependency in non-pregnant populations.A commonly cited reason for maintaining the 175 grams per day threshold is concern about ketosis. In the context of poorly controlled diabetes, elevated maternal ketone levels (ketonemia) have been historically linked to lower IQ scores in children (Rizzo et al., 1991). However, a 2021 review in Diabetes Care by Tanner et al. critically examined the available literature and concluded that the evidence was inconclusive and often confounded by coexisting malnutrition, acidosis, or hyperglycemia. The authors argue that ketones per se have not been established as causal, and that routine avoidance of ketosis in pregnancy may be based on limited or outdated data, calling instead for renewed research to better understand the role of nutritional ketosis in pregnancy, particularly within the context of controlled, nutrient-dense low-carb diets. Furthermore, the rationale for high carbohydrate intake during pregnancy often cites the glucose needs of the developing fetus. However, maternal hepatic gluconeogenesis is robust, and can likely meet both maternal and fetal glucose requirements even with reduced dietary carbohydrate. This raises a legitimate question about whether the 175 grams per day recommendation is physiologically necessary—or primarily a precaution driven by theoretical concerns.

CURRENT EVIDENCE

Evidence supporting the use of low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets during pregnancy remains limited and underexplored. This gap does not reflect a lack of clinical plausibility or interest, but rather a systemic hesitancy and insufficient institutional support for investigating nutritional strategies that deviate from conventional dietary guidelines. Current recommendations for a minimum carbohydrate intake of 175 grams per day during pregnancy are largely based on theoretical concerns—particularly regarding ketosis—rather than on robust, contemporary clinical trials. While animal studies have examined the effects of ketogenic diets during gestation, their findings are often conflicting, and their translational value is limited due to significant interspecies differences in placental metabolism, energy substrate utilization, and developmental timing (ref).

In contrast, recent human data from Muneta et al. (2022) provide valuable insights into ketone physiology during pregnancy. In a study involving over 600 mother-infant pairs and placental samples, the authors reported elevated levels of β-hydroxybutyrate (βHB) throughout gestation in both maternal and fetal compartments—including the placenta, cord blood, and cerebrospinal fluid—without any signs of adverse outcomes. Notably, βHB levels were physiologically high during the second trimester and declined closer to term, suggesting a natural role for ketones in fetal energy metabolism and development. The study also documented βHB concentrations up to 2.8 mmol/L in placental tissue and up to 2.3 mmol/L in cord blood. Importantly, pregnant women with GDM who were managed with a very low-carbohydrate diet avoided the need for insulin therapy, experienced weight loss without hunger, and delivered healthy infants without complications, despite the presence of measurable ketonemia.

Additional anecdotal reports further support the potential safety and benefits of carbohydrate-restricted diets in pregnancy. For example, in a case series of women with drug-resistant epilepsy, adherence to ketogenic diet therapy throughout pregnancy enabled effective seizure control and resulted in normal early neurodevelopment in the offspring (ref). Similarly, a woman with Glucose Transporter Type 1 Deficiency Syndrome (Glut1DS) maintained a ketogenic diet during pregnancy under close medical supervision, with favorable outcomes for both mother and infant, including healthy postnatal development (Kramer). In women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)—a common precursor to GDM—case reports have shown that ketogenic diets not only improved metabolic parameters but also restored ovulatory cycles and led to spontaneous conception after prolonged infertility (Palafox-Gomez). Taken together, these findings highlight a critical and overlooked research opportunity. Given the well-documented benefits of carbohydrate restriction in non-pregnant populations—including type 2 diabetes reversal, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced medication dependency—it is both timely and necessary to reconsider existing assumptions and design rigorous studies exploring the safety and efficacy of low-carbohydrate diets in pregnancy, especially for women with GDM.

CALL TO ACTION:

There is overwhelming evidence that gestational diabetes produces worse health outcomes for mother and baby that extends into the offspring’s adulthood, affecting subsequent generations. Careful examination and rigorous testing of the carbohydrate needs of pregnant women to define optimal nutrition has the potential to dramatically change the health of our nation.

Dr. Caroline Roberts and Dr. Greeshma Shetty, trained at John Hopkins and Harvard Medical School, are board-certified endocrinologists and key leaders at Virta Health. Virta has redefined diabetes care through their work in metabolic medicine, leveraging nutritional interventions and remote care to achieve unprecedented rates of type 2 diabetes remission and medication reduction.

Article Reference: Gestational Diabetes – References