Obesity in Children

Beyond Obesity and Overweight in Children: Insulin Resistance as The Root Cause of Pediatric Obesity and The Prescription of Low Carbohydrate Eating as The First Approach

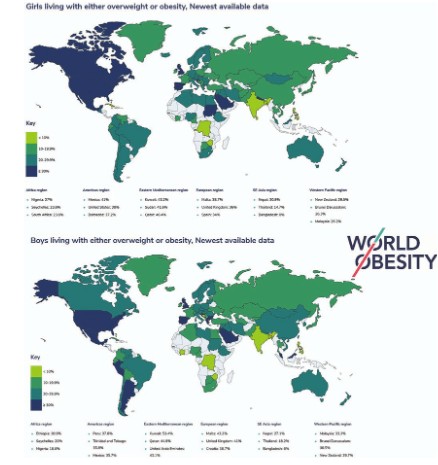

Pediatric obesity rates and weight-related comorbidities continue to rise despite increasing awareness. Nationally, the obesity rates among 20-39-year-olds is approximately 40%, as reported by the CDC[1]; this is a 300% increase since the 1970s.[2] According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2023 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Obesity, over 14 million children are affected by obesity[3]. Childhood obesity rates are approaching 20%, which is three times higher than in 1980.

The change in rates of pediatric obesity is alarming. The prevalence of obesity has doubled among children ages 6-11 and quadrupled among ages 12-19 from the 1970s to 2015, according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data[4]. We are failing on the world stage [5].

Global atlas on childhood obesity by the World Obesity Federation (ref 5)

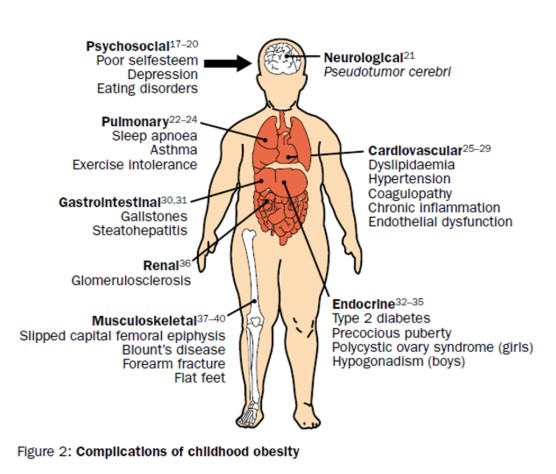

Studies show that approximately 80% of adolescents with obesity will continue to have obesity in adulthood [6]. Children with obesity are more likely to suffer from cardiovascular diseases [7] digestive disorders and several cancers, including breast, colon, esophageal, kidney, and pancreatic cancer in adulthood [8].

Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002 [9]

Healthy adolescents are expected to live into their 7th decade. However, obesity significantly reduces life expectancy and quality of life [10] which makes it a serious public health concern. It has an enormous impact on both physical and psychological health. Weight related comorbidities found in this population include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, osteoarthritis, and pseudo-tumor cerebri to name a few. Currently, 1 in 5 adolescents and 1 in 4 young adults are currently living with prediabetes [11]. In addition, pediatric obesity is associated with negative mental health consequences, such as poor self-esteem, anxiety and depression.

More children are now developing conditions that were once seen only in adulthood; this highlights that pediatric obesity should be tackled from a public health and policy framework and the root cause should be closely addressed. Furthermore, we are facing a national security threat as most teens in high school are ineligible to enlist in military service due to obesity. Only 25% of youth are eligible to serve in the military. Most are disqualified for conditions related to obesity and poor fitness [12] [13].

Defining Obesity: Increased Adiposity is the Real Pandemic

There is a call out now to abandon the BMI language in search of a more accurate definition of body fat which contributes to illness [14]. The term “overfat” is defined as excess adiposity that impairs health. Our intent is to be sensitive with the term “fat” which in many modern contexts is a negative term, but as clinicians we need to be specific about when excess adiposity contributes to poor health and when it does not.

We Have Evolved to Eat Nutrient Dense Low Carbohydrate Foods

Humans are omnivorous in nature, capable of consuming both plant and animal-based foods. This flexibility in food choices has allowed us to adapt to a wide range of environments and food availability. However, this industrialized society has come at a cost. These modern foods, with refined flour, added sugars, and vegetable oils, likely have contributed to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [15].

Although not prospectively studied, the observation of children and societies with low obesity rates have less processed and sugary foods [16]. In school breakfasts and lunches, which are based on the US Dietary Guidelines, children can consume over 200 grams of processed carbohydrates and sugar [17] not only in the form of sweetened drinks but also in added sugars and sweeteners. These sugar-sweetened items include breakfast cereal, spaghetti sauce, ketchup, baked goods, dressings and gravies, and the fruit cups. The number one product purchased with the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is soda. [18]

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends children receive no more than 6 teaspoons of added sugar daily, which is equivalent to about 24 g.[19] According to the CDC, the average daily intake of added sugars was 17 teaspoons for children and young adults 2-19 years old from 2017-2018 [20].

Sugars and fructose, especially from beverages, are highly problematic for metabolism, as reported by Bray and colleagues [21]. According to the report, during the American colonial period, the amount of sugar consumed by the average person in 1750 was just 4 pounds per year, which is just over 1 teaspoon per day. Sugar intake in the United States has increased by >40 fold since the American Revolution.

In addition, there are additive effects of sugar and screen time reported in the literature. A recent review of over 14,000 high school students collected across all states found that drinking 1 or more sodas each day while watching television or playing video games for more than 3 hours per day was the strongest predictor for obesity [22].

Screen-time also has another negative impact, advertising works against children from certain backgrounds. A recent report from the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity found that in 2017, 86 percent of television advertising on programs targeted to African Americans and 82 percent of ads on programs targeted to Hispanics were focused on junk food, sugary drinks, or other high-sugar snacks and candy [23].

These sugary foods fall into the category of ultra-processed foods, according to the NOVA Food Classification System [24]. Kevin Hall’s highly cited study also attributes processed foods to increased calorie intake when eating freely. In his study, he found that when participants ate the ultra-processed diet, their calorie intake was over 500 calories a day higher when compared to those who had the unprocessed diet [25]. This suggests that ultra-processed diets do not signal satiety as quickly and result in increased energy consumption and further weight gain. Ultra-processed food, sugar, and fructose have been strongly associated with obesity and metabolic illness whereas a diet lower in carbohydrates can improve metabolic health [26].

What We Are Doing Now Is Not Working

Interventions so far have done little to flatten the curve of the obesity pandemic as reported in Interventions for treating children and adolescents with overweight and obesity: An overview of Cochrane Reviews [27]. For over 50 years, we have focused on reducing fats when a long body of evidence suggests the opposite [28].

When we encouraged our population to reduce fats and increase carbohydrate, the epidemic of obesity escalated [29]. Efforts to reinforce fat reduction even in the context of trying to increase activity have failed. An extremely large database demonstrates this: the annual probability of achieving a 5% weight reduction was 1 in 8 for men and 1 in 7 for women with morbid obesity” [30].

If we are going to design the best treatments based on a defined disease, not merely obesity defined by BMI, we must examine the actual disease processes that children with obesity currently face. The 2023 AAP guideline focused on BMI but specifically excluded evidence around issues not directly related to weight. We make the case that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are the root causes of medically significant obesity and the cardiometabolic conditions that are associated with it. Both children and adults alike suffer from insulin resistance, however not all are obese. Furthermore, not all obese children have markers of cardiometabolic disease.

Intensive Health Behavior and Lifestyle Treatment (IHBLT), as described by the American Academy of Pediatrics 2023 clinical practice guideline on pediatric obesity, has limited effectiveness. The intensity and resources needed to provide this type of service in most communities would be difficult to scale, especially in those of low socioeconomic status. Even when this method is provided in a research setting, the mean weight loss is small. Attrition rates are also extremely high [31].

Other methods suggested in the AAP document are pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery, neither of which have long term data on children’s overall physical and mental health. Up until the newly approved GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, the effectiveness of anti-obesity medication for pediatric obesity was minimal[32]. The newly approved GLP-1 receptor agonists can be effective for children and adults in reducing insulin resistance and promoting weight loss by decreasing appetite and increasing satiety. However, the financial cost of these interventions is enormous and some individuals are unable to tolerate the side-effects. If GLP1 Receptor Agonists or surgery were offered to millions of children, our economy could not afford it.

We Must First Look for A Better Nutritional Approach

The Dietary Guidelines for America have failed to address obesity, and the scientific rigor has been challenged by National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM): “The process to update the DGA should be comprehensively redesigned to allow it to adapt to changes in needs, evidence, and strategic priorities.”[33]

Ebbeling, Pawlak, and Ludwig describe the crisis and potential solutions in the article: Childhood obesity: Public-health crisis, common sense cure:

“It is hard to envision an environment more effective than ours [in the USA] for producing . . . obesity”, yet the current medical view is now shifting toward genetics and medical treatments. The group is skeptical of this “because this epidemic was not caused by inherent biological defects. Increased funding for research and health care, focusing on new treatments, will probably not solve the problem of pediatric obesity without fundamental measures to effectively detoxify the environment. Although these measures require substantial political will and financial investment, they should yield a rich dividend to society in the long term.” [34]

The “dietary landscape” is indeed toxic for many children as this article describes[35]. A recent analysis of 240 of the most popular baby and toddler foods in the United States showed that 100 percent of baby food desserts, 92 percent of fruit snacks, 86 percent of cereal bars, and 57 percent of teething biscuits and cookies contained more than 20 percent of their calories from sugar [36].

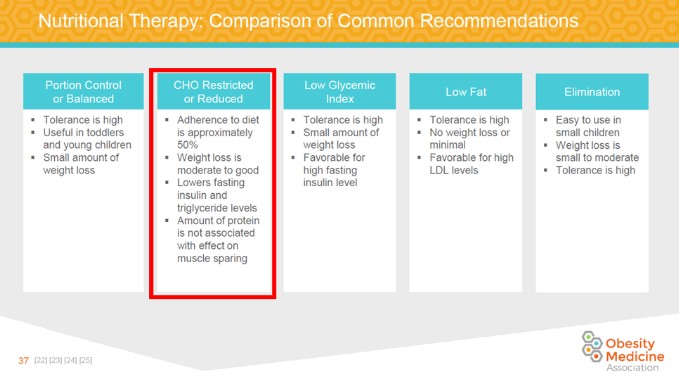

2022 Pediatric Obesity Algorithm p 37. Best Method is CHO Restricted/Reduced. Red Box is the author’s highlight [37].

Call to Action

Childhood obesity is still undefeated. We must then ask ourselves: “If we understand and are doing a good job with obesity then why are so many now so sick?” We present the model of insulin resistance, which is a driving force of this condition; the optimal way to reverse the insulin resistance is to reverse the hyperinsulinemia. To do this, we make the case that carbohydrate reduction should be the first intervention, or at least an option, for all children seeking treatment for obesity. The future costs will be borne by the US healthcare system if we do not address obesity with non-pharmacologic and non-surgical methods. You can’t fix healthcare until you fix health. You can’t fix your health until you fix your diet. Food is medicine and we argue that a reduction in carbohydrates is a powerful initial tool for pediatric obesity as it will target insulin resistance. We hope for our future to have more research, clinical experience, and policy in support of a low carbohydrate diet for children to address insulin resistance as the underlying issue at the neuroendocrine level.

“There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and [prevent them from] falling in.” – Desmond Tutu

“When a flower doesn’t bloom you fix the environment in which it grows, not the flower.” – Alexander Den Heijer

Dr. Mark Cucuzzella , a board-certified physician in Family Medicine and Obesity Medicine and professor at WVU School of Medicine who has treated patients with obesity and diabetes, including veterans and underserved populations. Dr. Cucuzzella is a leading advocate for low-carb nutrition and obesity and diabetes remission, pioneering hospital protocols and medical education to combat insulin resistance and improve metabolic health.

*Appendix- this piece is a short summation of a more comprehensive review by the author

Beyond Obesity and Overweight: The Clinical Assessment and Treatment of Excess Body Fat in Children Part 1 — Insulin Resistance as the Root Cause of Pediatric Obesity

Beyond Obesity and Overweight: The Clinical Assessmeent and Treatment of Excess Body Fat In Children

Part 2 — the Prescription of Low-Carbohydrate Eating as the First Approach

A comprehensive lecture by the author can be viewed here:

Pediatric Obesity San Diego 2021 https://youtu.be/cjEcbLSL35A